This post is a collaboration with Nick Maggiulli from Of Dollars and Data.

I read Nick’s book, Just Keep Buying, and the thing I loved most was how he backed up all his arguments with data.

I was chatting to him on Twitter about why I enjoyed his book, and he said, “If you ever want to collaborate on something (or want me to run a simulation of something for you), let me know.”

I had a topic I thought would be perfect to collaborate on, and this article is the result.

I’ve always had a problem with the 4% rule for early retirement.

It’s not because it’s bad or wrong.

It’s because it’s not for early retirement.

The 4% Rule: Why It’s Not Ideal for Early Retirement

My biggest issue is that it doesn’t account for the flexibility of most early-retirees.

It’s for standard retirement, and “traditional” retirees in their 70s or 80s aren’t likely to have as much lifestyle or spending flexibility as someone in their 30s or 40s.

By the time someone has reached the end of their career in their 70s, it’s likely they:

- Have settled on a level of spending they want (or need) to maintain

- Have no desire (or ability) to get another job, if the shit hits the fan

- Are bound to a particular area (or even house)

- Have a high percentage of their spending going towards essential expenses, like food and healthcare

- Are more sensitive to inflation (due to a high percentage of essential expenses)

Compare that to someone in their 30s or 40s who retires early and has:

- A more flexible lifestyle with less fixed expenses

- The ability to pick up part-time or full-time work, if necessary

- The freedom and/or desire to live in beautiful but cheap places, like Southeast Asia or South America, to reduce expenses without reducing their quality of life

- A high percentage of their spending going towards discretionary expenses (e.g. travel, dining, drinks with friends, etc.)

The 4% rule doesn’t account for any of that flexibility.

It assumes you’re going to spend 4% of your portfolio’s value in your first year of retirement, and then increase that spending with inflation every year after.

Speaking of inflation…

What About Fixed Costs?

In a recent Money with Katie episode with the guy who created the 4% rule, William Bengen, Katie brings up the point that 4% is already conservative because of the way it treats inflation.

It assumes you’re going to inflation adjust ALL of your spending every year, whether inflation impacts every expense or not.

If you have a 30-year-fixed mortgage, for example, your biggest expense may not be impacted by inflation at all!

Other Reasons the 4% Rule is Conservative

I recommend you listen to the entire Money With Katie interview, but here are a few other reasons from that episode that 4% may be overly conservative:

- The 4% rule was originally the 4.15% rule, but it was rounded down by mainstream media because 4% was easier to say/remember

- The 4.15% rule is now actually the 4.8% rule, based on Bill Bengen’s updated analysis (which includes additional asset classes)

But the Money Has to Last Longer?

So the 4% rule is conservative for a 30-year retirement, but don’t we need to pick a lower withdrawal rate for a 40+ year early retirement?

Yes, but not as low as you may think.

We explored this topic in depth during my interview with Michael Kitces (still one of my most-popular episodes of all time).

If you want to add 10 years to a standard retirement, you should decrease your initial withdrawal rate by ~0.6%.

And surprisingly, a portfolio that survives for 40 years is likely to survive for 50 or 60+ years (see my post on Sequence of Returns Risk to learn why).

Are We Back Where We Started?

So if the 4% rule is actually the 4.8% rule, but we need to decrease that by ~0.6%, aren’t we back to roughly where we started (i.e. 4%)?

Yes, but we haven’t accounted for early-retirement flexibility yet!

And that’s what this whole post is about.

Incorporating Flexibility Into Your Withdrawal Strategy

Before Nick started crunching the numbers, we went back and forth to figure out the best way to factor flexibility into the withdrawal rate, and here’s what we came up with…

Discretionary Spending Percentage

First, figure out the percentage of your spending that goes towards discretionary expenses.

Discretionary expenses are any expenses you feel you could do without, if necessary.

Calculate New Withdrawal Rate

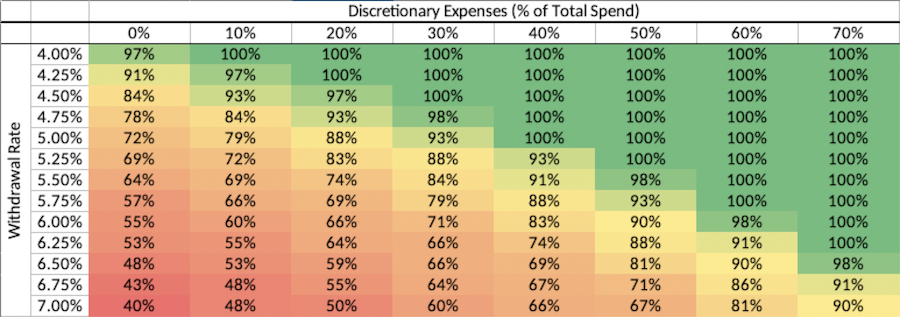

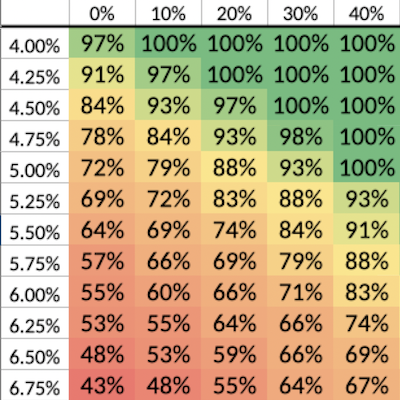

Once you have your discretionary spending percentage, find it on the following table and then pick a comfortable success rate in that column to find your withdrawal rate (the table assumes an 80/20 stock/bond portfolio allocation).

Or, if you have a FI Laboratory account, you can use the calculator I created to compute your withdrawal rate using this method.

If you don’t have a FI Laboratory account, you can get one for free here!

Withdrawal Rules

Now, you should have a withdrawal rate that is higher than 4%, so you could retire sooner (because a higher withdrawal rate means you’ll need to save up less money to cover your annual expenses)!

There’s no free lunch though (you can’t just withdraw more every year and expect your portfolio to last as long as it would have with the 4% rule), so there are some simple rules you have to follow for this strategy to work:

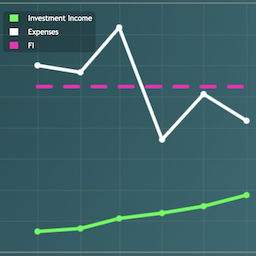

- While in a bear market (>20% off of highs), withdraw $0 for discretionary spending

- When the market is in a correction (>10% below highs), withdraw 50% of your discretionary budget

- All other times, withdraw your entire discretionary budget

Let’s see how this would work with an example…

Discretionary Withdrawal Rate Example Scenario

Let’s say a retiree has $1M in an 80/20 portfolio.

Using the 4% rule, that would allow for $40,000 in spending in year one, adjusting for inflation each year thereafter. With this portfolio and withdrawal strategy, there is a 96.55% chance of success (across all 40 year periods from 1926-2022).

But can we keep the same probability of success while withdrawing more with our new withdrawal method?

Yes, if the retiree follows the rules…

If they have 50% of their spending as discretionary spending, they can withdraw 5.5% (instead of 4%) and still have a 98.28% probability of success (across all 40 year periods from 1926-2022)!

Using our $1M portfolio as an example, in year one they would withdraw $27,500 as essential spending (half of the 5.5%) and then withdraw:

- $27,500 as discretionary (if the market is <10% from its highs)

- $13,750 as discretionary (if the market is >10% off its highs, but <20% off its highs)

- $0 as discretionary (if the market is >20% off its highs)

While the essential spending adjusts upwards with inflation every year, the discretionary spending does not move with inflation (research shows that retirement spending tends to decrease over time, so this gradual decrease in real spending power should be manageable, while also ensuring essential expenses are always covered).

So in year two, after a year of 5% inflation, this person would withdraw $28,875 for their essential expenses and then either $27,500, $13,750, or $0 for their discretionary expenses (depending on the past year’s market performance).

Using this method, you’d have roughly the same probability of success over 40 years and, in most years (i.e. good years), you could withdraw more money!

Or, you could use this method to retire years earlier…

In this example, the person would need to wait until they hit $1 million to retire to cover their $40k of annual expenses, using the 4% rule.

If they use this new method instead though, with a 5.5% withdrawal rate, they’d only need to save up $727,273 to withdraw the same $40k for expenses (although, they’d need to cut back on their discretionary spending in down years).

Other Benefits of this Method

This method allows you to spend more and/or retire earlier, which is great, but it also comes with additional benefits…

Buffett’s quote about inheritance applies nicely to early retirement – “A very rich person should leave his kids rich enough to do anything but not enough to do nothing.”

I’ve seen a bunch of early retirees (myself included) race to the FI finish line, only to be left disoriented when confronted with the fact that money is no longer a motivating factor in their lives (and therefore, they could do “nothing”).

Having this discretionary withdrawal strategy seems to solve a lot of the problems I see with full FI:

- It encourages you to focus on reducing your fixed costs (i.e. the expenses that really matter) but lets you relax with your fun/discretionary spending.

- In down years, you’re forced to reevaluate your discretionary spending (so you don’t just keep mindlessly spending on things that you may not provide value anymore)

- It gives you a pot of money specifically for discretionary spending, so you’ll hopefully be more likely to spend on fun things (rather than just keep saving and saving, like I did).

- When you reach your number, you have enough to do “anything” but not enough to do “nothing” (unless you’re happy with $0 of discretionary spending during bear markets).

- Money is still a motivating factor in your life, because you may want to have some income coming in during down years

- Since your spending/lifestyle is changing year-to-year, you’ll hopefully appreciate things more (rather than just get into a routine of spending/doing the same things)

What if my porfolio’s performance differs from the market?

Just because the overall stock market is tanking, that doesn’t mean my portfolio is down 20%…shouldn’t the discretionary budget be calculated based on what my own portfolio is doing?

We thought about this, but we liked the simplicity of using the market as a guide. All the financial headlines will be screaming, “Bear market!!” when the overall market is down 20%, but nobody cares what your portfolio is doing.

Plus, the time to tighten your belt and be more cautious is when there’s fear in the streets. When the overall market is in a big correction, the real economy may also start to falter. That would make it harder to find work, if necessary. So it makes sense to tighten your budget when the overall economy is on shaky ground.

What if I don’t want to cut back so much during down years?

That’s the beauty of the strategy…you get to decide your discretionary percentage.

So if your fixed/essential expenses are 50% of your budget, but you know you want at least 15% to spend on discretionary spending to enjoy life (even in down years), then just treat 65% of your budget as essential and say that 35% is discretionary. You’ll have to work/save longer, but if that results in an early retirement that you enjoy, it’s worth it.

What do you think?

There seem to be a lot of benefits to thinking differently about your essential and discretionary expenses when it comes to early retirement, but what do you think?

Do you like this method, or is it too complicated/risky? Are there any other benefits/downsides I didn’t mention? Let me know in the comments below!

Just Keep Buying

Once again, huge thanks to Nick for taking the time to run all these simulations!

I probably wouldn’t have gotten around to writing about this topic, had it not been for Nick’s kind offer. So if you liked this post, be sure to thank him by checking out his excellent blog (Of Dollars and Data) and book (Just Keep Buying)!

Nice. I love that y’all put numbers to flexibility.

One other thing to those who worry. Be confident. If you were smart or resourceful enough to figure out how to save a a million dollars at 40, you’re also smart enough to come up with a plan when the shit hits the fan.

Carry on.

Nailed it with this more flexible strategy. Right balance of simple/practical yet more precise for how this all actually works. Thank you both for the work.

Why not just run the portfolio at a 5% dividend clip and take 2 percent from stock sales?

Flex rate is the key! Check out the rich, broke or dead simulator

I also like the Rich Broke or Dead calculator for the visualization of mortality. It’s a bonus that it has a spending flex option.

I

I love this article. I agree with every word in it.

The only thing that jumps out as truly ‘missing’ for the early retirees is that should they want to keep on spending despite having a down year, taking on basically any job (prioritizing one that is rewarding in other ways) and using that to fund discretionary spending can achieve basically the same thing, with just a minor imposition on time in exchange. If essential expenses are already taken care of, then having a transition year of the Barista FI life (or realistically for most people capable of achieving early FI, taking on some freelance work or working gigs related to their former career) can achieve that same massive shift in nest egg sizing required to be financially independent. I would even go as far as to suggest doing a deliberate transition year for those with anxiety about really letting go because you can actually live exactly what a ‘worst case’ year during that early retirement phase can be, and not having to burn large percentages of that early invested capital is what really drives the ability of those other good investment years to start converting gains into a FatFIRE portfolio on their own.

Agree entirely. That supplemental income in early years is massively impactful ‘insurance’. Is there a usable calculator that lets one factor this in? Need to check out the FiLab calculator, not sure I’ve tried that one.

Check out ProjectionLab. It lets you do all sorts of things like that.

You can do a trial…don’t log off. At some point, you have to purchase it to even see the trial stuff you did but I found it helpful as my first step for a pre-approved mortgage loan application. Then Mad Fientist’s spreadsheets!

Only some careers will realistically allow for freelance or project work. Age discrimination is real. People who have not yet retired and retirees with lots of incoming income seem to be the ones saying “you can always get some more work if you need it.” Retirees who are living just off their portfolio are a LOT more sanguine. This all will vary with facts and circumstances and is no more generalizeable than what proportion of spending “should” be discretionary. You know, like a lot else in personal finance!

I agree completely about age discrimination. Some fields are worse than others (mine is a notoriously female dominated profession) and I began noticing it as early as age 40.

I might also mention that the 4% rule doesn’t take into account dividends I believe. That said VTSAX or VTI gives off about 1-1.5% dividend each year.

Yes is does, it is based on total returns.

This is an amazing article. Thanks so much for explaining this, I was just putting this months numbers in my MadFI overview

This smart guy argues for a 2.7% rule (but this assumes no flexibility as far as I can tell, making it very conservative).

Ben Felix: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1FwgCRIS0Wg

Love Ben Felix’s channel! Based on Ben’s video and this article I have now two aspirational net worth numbers on my planning spreadsheet: One for the conservative 2.7% withdrawal and another one for the discretionary 6.25% withdrawal. I already reached the latter, but since I plan to work part-time at my current enjoyable job until 2029, looks like I will reach the first as well (rock solid retirement!).

Interesting post as always, thanks! The ability to vary spending from the simulations I’ve run is certainly powerful at improving the success rate of a given plan. The challenge for me is, when you’re in it, it’s tough to know when to actually start throttling back the spending or turning it back on. For instance, if you use 10% or 20% as a trigger, do you maintain those lower levels of spending until the market is back up to the original level? As a saver, it would be tough to “turn it back on” after a long bout below the peak.

The SP500 was at 4766 in Dec 2021, dropped to below 80% within 6 months, and is still 12% below the peak 18 months later. If I had retired at the end of ’21, I’d still be running at the “essential only” rate and it’s highly likely I’d be going back out for another job…essentials only for a long duration isn’t too appealing for my better half!

I realize the point of your post is that early retirees are different, but if I were to retire today at 52, it’s not that “early”. GCC has a decent post recently on the social security factor for those of us who aren’t so early, but this one is also super helpful, so thanks. Any more insights you can share on your thoughts on the mechanics of this would be helpful.

I have the same critique of the spending rules provided, which is how do you know what stage you are in at any given time? I really liked Brandon’s thoughts on how to catch a knife in a post from a few years ago, but same problem of how do you know what stage you are in.

Hi I’m im similar position, at 55, do you have link to that post? Thanks!

It was in a link from a recent article, but is actually an article from 2019. Guess I had forgotten it! Here it is

https://www.gocurrycracker.com/spending-future-social-security-income-now/

Excellent — we are finally getting people in the FI community to stop being overly pessimistic (“but that was only good for 30 years and then my portfolio probably turns into a dogs-and-cats-living-together-mass-hysteria pumpkin”) and start taking control over their withdrawal strategies using the obvious tools at their disposal.

Personal Inflation is Personal! And if your lifestyle inflates at less than the CPI and/or you employ a variable withdrawal strategy, your withdrawal rate can easily increase by 0.5-1%.

The one thing you are missing here is what Bill Bengen also said to Katie — that simply holding a better diversified portfolio that is designed for drawing down on can also increase your safe withdrawal rate. Here’s a clue and your homework assignment — an 80/20 two fund portfolio ain’t the secret sauce — Bill says DON’T use that kind of two-fund thing just because he was stuck analyzing it in 1994 because that is the data he had available.

So what does he recommend for a portfolio then if not the 80/20 two fund?

One that is roughly 55% in equities with a small-cap value tilt and also includes exposures to alternative investments. Basically, Bengen says that if he did the same research he did in 1994 with a better portfolio, the results would have indicated a 4.7-4.8% 30-year safe withdrawal rate.

The following portfolio has a 30-year safe withdrawal rate of about 5% over the past 97 years — and its not really optimized in any way: 27.5% S&P 500, 27.5% small cap value stocks; 25% long-term treasuries; 15% gold; 5% t-bills. Extend it to 40 years and its 4.63%; 50 years and its 4.26%. And this does not account for the variable withdrawal techniques discussed in this article.

The corresponding numbers for the 80/20 portfolio discussed in this article are 3.86% (not even 4%) for 30 years, 3.66% for 40 years, and 3.49% for 50 years. Honestly, I don’t understand why someone would hold that in retirement — its really an accumulation portfolio.

All calculations in the last two paragraphs were conducted using the Toolbox calculator found at Early Retirement Now.

Thank you, Uncle Frank. Risk Parity Radio Podcast! And, thanks to Mad Fientist for great article which echos what Paul Merriman was saying about varying distributions out of his own portfolio.

Almost like you do a whole podcast on this exact subject…

…or something.

I’d love to see your analysis of the future of the housing market. With the boomer generation owning such a large portion of real estate wealth (44%), the average age of the boomer generation (~68y/o), and our current life expectancy (78 yrs), a huge portion of real estate is going to be inherited soon, peaking in about 10 years. What will this do to the overall housing market? I wonder if we will be flooded with homes no one can afford, thus dropping prices significantly.

That’s an interesting point!

Life expectancy for the nation isn’t the same as life expectancy for the wealthy. Sure, we have Boomers in our family who have passed in their 60s and 70s. But more broadly, the educated Boomers with access to good food and healthcare are going to live longer. Otherwise, I like your thinking! It’s just going to play out more slowly.

I was wondering this too, because my dad’s house (paid off long ago) in a high property tax area…his annual taxes are more than my entire mortgage.

I doubt it. Some markets may see drops (indeed some already are), but Millennials are the largest generation in history and are just entering their prime homebuying years. This creates nearly insatiable demand for the foreseeable future. That demand is colliding with extremely limited supply, hence prices are continuing to rise, especially in desirable places. In my neck of the woods, there’s still a bidding war for every house that goes on the market, even with the current interest rates.

Part of the problem is folks that locked in ultra-low interest rates don’t want to give them up, thus keeping houses off the market.

As a generality, Boomers will pass wealth down to children who will sell if market favors, or rent, house hack, sell their cheaper home that is easier to sell and move into their parents nicer house, etc.

Kids who grew up hearing “IF social security exists when you retire” aren’t going to just sell for tons below perceived value, their ability to retire may often rely on good use of inherited wealth to close the gap.

I speak with the experience of someone who retired at 56 and is now 61. The biggest issue I have with the article and with early retirement in your 30s and 40s is that at that relatively young age, what you may perceive as your spending may change dramatically if and as your life changes. For instance, you may buy a home instead of renting an apartment — We didn’t buy our house until I was 38 — which results in a lot of additional expenses, many not discretionary (when the refrigerator or boiler or dishwasher or washing machine or dryer goes, there isn’t much discretion in replacing it). You may have children (or more children), which increases your food bill, phone bill, car insurance, extracurricular activities, college costs, vacation costs, umbrella insurance etc. What I am saying is that there are lot of fixed expenses that only arise as you get older and your life changes that you may not contemplate when you are younger. I am in no way trying to discourage folks from retiring early. I did and am glad it did. I just think you need to be flexible not only with your spending in retirement but in actually determining what your spending might be and how it might change.

You’re correct, and this is good advice to keep in mind. I’ve been surprised at how significantly my spending has increased from many of the things you’ve mentioned, kids, house, etc.

I agree with the points that Russ and Andy are making. We have been early retired (retired at 50) for 9 years. Our experience has been that unforseen expenses (house expenses, car, family caregiving, health issues) do arise, and it is hard to plan for them. Moving to lower cost areas (to reduced non-discretionary expenses) does work for some, but the drawbacks often result in the need to travel more for cultural opportunities, healthcare, visits to family and friends, etc.

Totally agree. I love the FI movement, but if it has a blind spot, this is it. Kids and all the costs that go with them are probably the biggest non-discretionary spending category that a younger person would have difficulty understanding, let alone planning for. I think many folks solve for this by not having kids (which is fine), or only having one. But if you come to the movement later in life like I did there’s a good chance you already have kids, which greatly reduces your flexibility. Or you may retire early and then decide to have kids, which will increase your spending in the ways you note.

Cal.

Even Kitces says 3.5%. I’ve never heard anyone recommend 2.7%.

I disagree w/ this article somewhat. Some FI people have kids.

My costs will go DOWN in 10 years when the kids move out. Then Social Security (or some portion of it) will kick in 10 years after that.

So, my costs are front loaded. Paying for everything X4 is expensive… even if you’re frugal.

I think you all should look at the earlyretirementnow.com safe withdrawal rate series before boldly launching into retirement with a 4%+ withdrawal rate and reliance on “flexibility.”

I second that. Flexibility can be a two way street. ERN has a good description of how long you may have to be flexible for. I love this blog, but it’s nice to get ERN’s perspective. Nick seems like a smart guy who’s great with numbers, and has a BA In economics. Karsten seems like a smart guy who’s great with numbers, and has a PhD in economics, is a CFA, and worked for the Fed. Qualifications and title’s aren’t everything. But maybe they count for something?

100% this. I do love Nick (and own the book/read all his blog articles etc..), I think he breaks it down into the right level for the vast majority of people across FI-space (from the new starter to the 90%ile FIREr) but the exhaustive analysis ERN has done really is useful and significantly adds to my overall info base.

Perhaps I am just belt/braces type guy (echoing many other articles talking about the fact the majority of FI style people are over-savers/over-analytical types) – but I place a lot more store in the ERN calc’s. Plus with 2 kids trying to have a few backups is useful. ERN’s numbers do go sub 3% if you look carefully

Lastly there is very little analysis on the deduction for fees in portfolio (one article models it at 50% of the actual fee as a drag), and taxes. So for me I target 3.25% less 25bps for fees, and then 25% tax rate = 2.5% post-tax SWR (tax rates higher in Australia, but also am looking at a fatter FIRE)

2.5% is beyond cautious and approaching the absurd for me. Even with zero real investment returns, it would take you 40 years to get through your pile at that level of withdrawal.

2.5% is overly conservative, but whatever allows you to sleep at night I guess. I am surprised by the 25% tax assumption. Returns in super are only taxed at 15% pre retirement and zero thereafter, dividends come with franking credits so no tax there either, and capital gains are taxed on only 50% of the gain at your marginal tax rate, which is not likely to be the top given all the tax breaks you get. Capital gains tax might be 15% of the gain. And f course no tax on draw downs of your stash. In summary tax will be much less than 25%.

ERN has made an analysis of this post and – he does not agree. https://earlyretirementnow.com/2023/06/16/flexibility-swr-series-part-58/#more-74866

At the moment I am looking at the Living off Your Money chapter on flexibility.

Biggest problem is to find data when you do not have USD as currency – it makes a difference!

Love this analysis but not sure i agree that discretionary spending doesn’t need to get adjusted with inflation especially for early retirement. Do we really think that someone that retires at 35 will DECREASE their inflation-adjusted discretionary spending by age 40?

Yes! That’s the exact point that I disagreed with. If things are going to cost more because of inflation, then saying that my optimal/desired discretionary dollar amounts will remain fixed (even during good market years) over time is equivalent to making the assumption that I’ll somehow want to spend less as time goes on. That seems like an incorrect assumption to me, when looking at my adult life up to this point. I’m not saying I should try to support crazy lifestyle inflation, but allowing my spending to go up as inflation goes up feels like a very reasonable starting point.

Maybe Mad Fientist could point us to the research he mentioned here? “(research shows that retirement spending tends to decrease over time, so this gradual decrease in real spending power should be manageable, while also ensuring essential expenses are always covered)”

That being said, the flexible spending strategies presented are pretty solid, with easy-to-figure thresholds: within 10% and 20% below highest market point. And if nothing else, this article made me calculate my discretionary spending %, which was a surprising eye opener. I’d been tracking spending with Mint, but hadn’t looked at the various categories with a critical eye in a long time.

Look up David Blanchett and “Retirement Spending Smile” for endless research about spending in retirement and why it increases at less than the usual inflation figures. If you are looking for a “average” figure, you can use “CPI minus 1%” as Morningstar did in its recent analysis/paper in December 2022 after consulting Blanchett.

But better simply to track your own spending over time and use your actual numbers.

I appreciate you tackling the spending side of SWRs. Your methodology is very close to the Guyton-Klinger guardrails strategy so a reference to them would have been nice to see. I think it’s problematic to talk about the 4% rule without noting that it has survivorship bias in relying on US data (Canada and Australia being the other markets that would have supported 4%). Recent academic research suggests that removing the survivorship bias can reduce 30 year SWRs to as low as 2.26%.

Have you read the paper? Do you really plan on putting 40% of your assets in speculative bonds in non-reserve currencies? That is what that paper effectively assumes for most of its data — that you will invest entirely in home-country bonds, regardless of how risky they are and how bad your country’s currency is. Don’t forget to rebalance into even more of them when the country gets invaded in a war.

But if you don’t plan on making such investments, why are you relying on something that assumes such investments?

This is so helpful! I feel like it pairs nicely with the idea of FU money from JL. As a housewife with a gaggle of children, who loves to crunch numbers, I can completely attest to the flexibility of expenses.

Thanks for this article- interesting to consider as we are feeling closer to pulling some sort of trigger.

This is cool to consider, but I always get confused since I plan to baristaFIRE in some fashion indefinitely maybe until 70s or more, not 100% sure how it will shake out. I imagine some years will have more income than others. I’m guessing most here (including….my husband) are looking to be done working forever. I think if people are open to earning some income later on down the road, even getting a job if need be, it makes a huge difference. In those years you can let your stash keep growing. Basically the more flexible you can be the better chance your stash will last you. Same goes with the basics- if you have your house paid off, or are willing to move to a lower COL area, makes a huge difference.

Wish there was a calculator out there that considered:

Which accounts my money is in (pretax IRA/401k, post-tax IRA/401k, hsa, brokerage, other)

Money earned in FIRE

Expected social security payout

Lump sum contributions (for us we might sell our house at some point and invest it for a number of years before buying something again, if ever)

There’s a good one at spark rental but not specific enough for my needs. Does anyone know if/where something like this exists? I guess if this was so easy everyone would be doing it though!

Yes, that calculator exists. It’s called CFP

ProjectionLab can do all of that for you.

I-ORP.com is a good one I recently found

NewRetirement.com does all that and more.

I read some of the comments here trying to deduce a “new recipe” to replace the old 4% recipe. My interpretation of the article, which I agree with, is the importance of (1) being confident to be flexible and not relying on a set recipe (make your own!), and (2) providing some math to support that confidence.

Yes, life style changes, often in unexpected directions. But that’s precisely why we should give ourselves the permission to get rid of the 4% FI number blinders, and embrace our biggest asset as (present or perspective) RE: flexibility.

Yes, totally agree. The maths is backup. The lesson here to me is more like ‘look, tbh it’s so variable when you’re young as to be unspreadsheetable. Just go for it’.

Which seems to be borne out by pretty much any post early-FI story doesn’t it: opportunities to make money that don’t even feel like work just tend to fall in your lap; your post FI interests somehow start making you £££. And because you’re working from a frugal baseline, that ££ ends up covering a big chunk of your expenses, way more than whatever variability there might be in any ‘model’.

I really appreciate this article and the accompanying calculator.

I’ve noticed that my core spending is consistent but variable spending can change drastically. The variables are usually related to travel and home improvement. While some of the home stuff feels necessary, most of it has been intentional projects that we planned out, and we were able to delay big stuff until we were comfortable spending the money.

Great article! I totally agree and have for long said myself that the 4% withdrawal rate is too low and not realistic for FIRE. Spending patterns can and will change according to how things go. The 4% rule was meant to provide a 100% (or close to it) success rate no matter how bad things get. We all know that if things get bad we will naturally throttle down our spending on the discretionary side of the budget to keep our numbers positive. I think the 4% rule causes way too many people to delay FIRE that don’t need to.

I like this new way of thinking about RE! Reminds me a lot of Ramit Sethi’s conscious spending plan but with a FIRE twist.

By “any 40 year period,” was the analysis done using annual data or monthly? 57 annual 40-year periods versus 684 using monthly.

Looks like I’ll be spending the weekend categorizing my spending. I wonder if motor racing expenses belong in essential or discretionary?

Actually the answer’s obvious… essential.

If you’re in your 30s or 40s and savvy enough to have saved $1 million, your real task is not to tinker with your safe withdrawal percentages, it’s to figure out how to embrace the fact that life is fundamentally uncertain, the answers aren’t in a spreadsheet, and you really have got this :-)

It’s not realistic to never adjust your discretionary spending for inflation. Do you really think that if you currently eat out once or twice per week that you will reduce that to once or twice per month after 40 years?

Good stuff. Can you discuss how your wife making money affects being able to retire early?

It seems like having a wife earning a healthy income helps men retire early.

I really liked this article and the rule-based way to determine how much you should consider withdrawing. Practically speaking, what’s the best way to apply it?

* Check the market each morning? Probably not.

* Watch the news and when the market drops change your spending until it goes up again?

* Check each quarter? Each year?

Also when we say 10% off highs, is that ever, or compared to what period?

Lastly does anyone know of a tool or site that indicates if we’re in a bear market?

I agree with some things but not that at 30s or 40’s you’ll have more flexibility than at 60 or 70s! When you’re in your 30s or 40 you’re at your career peak and probably in very demanding jobs, trying to save and having to balance life with kids and heavy workload.

When you retire you have way more flexibility to do or not do things! I wouldn’t try to use an SWR higher than 4% even with flexibility. It’s very risky and the US is not what it used to be post WWII, it’s in decline

Exactly. I started reaind this artcile and thought exactly that. This part:

“It’s for standard retirement, and “traditional” retirees in their 70s or 80s aren’t likely to have as much lifestyle or spending flexibility as someone in their 30s or 40s.”

This is exactly the opposite. Who was flexibility in your 40s with kids, demanding jobs and the weight of the world on their shoulders! At 70s you’re done with all that and then you should have way more flexibility, granted not energy or vigor to do much but still, you can.

Good point. But I’m not sure you can make a blanket statement that ties lifestyle flexibility to age. Rather, your flexibility at any age really comes down to how many others are relying on you and your income. I’d quit my day job tomorrow if I didn’t have to support a family. If you don’t have kids (or they’ve left the nest), you have many more options. In my case, that’s at least a decade away LOL.

I don´t agree that USA is in decline. A period of heavy problems etc I am sure. But also still no1

https://www.visualcapitalist.com/sp/a-geographic-breakdown-of-the-msci-acwi-imi/

https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2023/08/23/americas-astonishing-economic-growth-goes-up-another-gear

Or as Buffet said, and I am paraphrasing: “I don´t know anyone hos has bet against USA and won.”

We still only have one superpower.

I’ve taken a simpler, less granular approach in my 4 years of retirement, but with the same goal of flexibility.

Each year, my budget is created by averaging a static and dynamic withdrawal rate:

* Static – calculated on year 0 and adjusted for inflation each year

* Dynamic – recalculated based on my net worth each year, as though the current year is year 0

I’ve found that to be a nice balance of flexibility and predictability. It doesn’t require me to split out discretionary spending, but in down years, I fully expect to either tighten the belt or find some work to supplement the income.

interesting approach.

I like this idea. It allows you to adjust, good or bad, based on portfolio performance and should take some of the bumps out of the road so to speak. It will also be interesting to be able to compare how close it ties in with the traditional 4%+inflation standard.

I agree. The 4% rule is a very safe / conservative rule of thumb. A generic rule of thumb. We forget that to fail the 4% rule you need to be landing the plane for over 20 years. If you know you are failing (Maybe you hit that bummer sequence of return risk) you would also have to do nothing for 5/10/20 years. You have time to be flexible. You know you are just as likely to fail the 4% as to be in the top % and be making mega returns- please spend it. We are not generic rules of thumbs we are all landing our own planes over a long time. Stay flexible.

Check out the Engaging Data calculator. It was called Dead or Broke I believe. Money Flamingo did a good writeup on flexibility a while back and how it helps you pull the plug earlier. Works just as well or better in a Barista FI scenario as well. I don’t really agree with the flat discretionary spending. Would love to see the research!

Another item as it relates to fixed cost is that at some point the mortgage will be paid off. Interest rates dropped in 2021 allowing many people to refinance and lower that fixed cost. Eventually with a paid off home one can also consider a reverse mortgage as they are eligible age wise

Safe withdrawal rate calculations are useful for the initial ballpark estimates. But to really fine-tune my model and account for the Smile Spending curve (David Blanchett PhD), social security, annuititaxation options later in life, etc requires more than rules of thumb. My current favorite calculator is Maxifi. It took some effort to fully comprehend how to use it but it is incredibly powerful at Monte Carlo simulations, optimizing your future options to tell you the absolute maximum you can withdraw each year. Unlike SWR rules of thumb, you can model your own chosen portfolio and withdrawal rules.

Have you seen Projection Lab?

Excellent article and comments.

I’ll be retiring soon and I’m categorizing my expenses into 3 buckets: Essential (60%), BAU (Business As Usual) Discretionary (15%), and Retirement Discretionary (25%). In my view, my true flexible discretionary is 25%.

I consider BAU Discretionary almost as Essential, you might consider it as the MVR (Minimum Viable Retirement) Discretionary that I’m spending today before retirement. It includes restaurants, Netflix, and other basic Discretionary items that are Essential for retirement. If I can’t handle that type of minimum discretionary spending – regardless of what the market is doing – then I shouldn’t be considering retirement. It likely means I need to save more.

Retirement Discretionary, to me, is truly the type of spending that is flexible. It includes things like travel, retirement toys (e.g. RVs), etc…

Also, Intermittent Essential expenses (new car, new roof for home, washer/dryer, etc…) can be forecasted. I’ve built them into my Essential expenses by using expected cost / expected duration. For example, I might budget and put into a sinking fund $6,000 annually for a new car in 8 years. So, $48,000 / 8 years is $6,000 I’ll put into a sinking fund. I’ve got 10-15 expense types (car, roof, AC unit, etc…) going into that sinking fund that covers expenses that occur in duration of longer than 1-year.

I’m retiring at 60 (with a 25-year corporate pension) and I will be spending more than 4% SWR in the first 10 years. At 70, taking social security means (for me) that I’m probably not going to need to spend ANY of my portfolio unless I truly want to be a big big spender past 70.

Thanks for the article and insightful comments.

Is the 4% rule before or after TAX?

You need to account for the taxes. So, if you withdraw $40,000 and trigger a $5,000 tax bill, you’ll need to budget an extra $5,000 in next years spending plan/withdrawal to pay the tax bill in April.

Very cool so see this backed with numbers, and “rule-ified”

I’d love to see one that does the reverse. When the market it up, cut spending to reap the rewards of the bull, when the market is down, enjoy the fruits of your labors, while prices are down, in a normal economy anyway. Not one that was driven down by out of control inflation. During normal “down” times, costs deflate as well, so not only do you have more to spend, you are getting more bang for your buck. It wouldn’t apply in the current down market, which adds another variable that one has to watch. That’s the theory anyway, but would need to see numbers to back it up, it could be bunk.

I think this flexibility becomes even more powerful if you combine it with a flexible withdrawal strategy. It seems to me that the main risk to your long-term retirement funding is sequence of returns risk, so what I recommend-to/implement-for my clients in retirement is:

– If the stock market is down >10% from its peak, we fund their current expenses by selling the bonds in their portfolio

– If it’s <10% from a peak, we sell stocks, and

– Once the stock market gets back to the previous peak, we replenish the bonds up to 5 to 10 years of projected spending (whether 5 or 10 years depends on the clients' risk tolerance).

It seems to me that this is why I have bonds in my portfolio – to buffer against stock market downturns, and BTW, this also means I only hold short-term bond funds because medium and long-term bond funds don't provide this buffering in high inflation years like 2022.

It would be great to have you and Nick add this to your scenarios, because I predict that adding this flexible withdrawal strategy to your flexible spending strategy that is outlined in your post would add to your success rate (and therefore the allowed withdrawal rate).

Absolutely agree! Regardless of the withdrawal strategy determined percentage, one should always endeavor to “buy low sell high”.

Should “self funding” of long term care (nursing home at the end of one’s life) enter into any calculations for a couple for withdrawal rate? My spouse and I are 49, madly saving for retirement and two kid’s 529s (and both working). I keep reading that long term care insurance is now horribly expensive- years ago when it was more affordable, that was due to a screwup by actuaries. So without having studied the situation much (because I’m prioritizing retirement savings and 529 contributions), I’m assuming I will be “self funding”- and I’ve always wondered if this should affect my withdrawal rate once we do retire.

Thanks!

The dark & scary, black-swan, topic of LTC! (Insert Jaws theme music!)

Financial podcasts & articles ignore LTC or it’s discussed with confusing generalities. There is no meaningful discussion of this “great-white shark” portfolio killer waiting out there for some unfortunates. Have too little money, you get Medicaid. Have way too much Trust-fund money, you are all set. Save just enough to comfortably retire and the LTC shark will devour all your assets until you die & leave your partner in poverty.

The only book I read so far that talked about the numbers behind LTC was “Retirement Planning Guidebook: Navigating The Important Decisions For Retirement Success” by Wade Pfau. I found Wade’s LTC chapter (& book in general) very interesting and insightful. Lots of charts, statistics, and cost analysis which I liked and helped me think about issue. I suggest you give it a read.

I am planning a Fat-FI, so my assets will grow enough by 80 to hopefully self-fund an expensive LTC event without devastating my partner’s retirement (or visa-versa).

Where are the simulations? Do you post some case studies, e.g., of the Sep 1929 or Dec 1968 cohorts? The 5.5% flexible rule likely boils down to a ~4% rule again for the worst-case retirement start dates if you have to cut your spending by 50% for extended periods. Hence, you withdraw about the same, on average, as under the old 4% rule.

Also, most of the recent Bengen work is questionable: Raising the SWR with small-cap value stocks might have worked in historical sims, but the SCV premium is pretty much gone going forward. Moreover, the “we have a lower personal inflation rate with a mortgage” narrative is nonsense. I debunked that in my SWR Series Part 57.

Can you discuss more on the SCV premium being gone going forward? I have a SCV tilt in my portfolio and your statement makes me question if I should…

The only problem I see is in down years, I won’t play golf as much and my game might suffer. Ha! :)

Other than that, great article and well written. Thank you!

Too complicated. Discretionary spending just continues on a downturn until you magically hit the negative number? And, like some have mentioned, that just stays $0 until the market is back up? Could be a LONG time with no discretionary spending.

Exactly this. Think back to the time period between the months of Dec 2000 and July 2012 (140 months). With the exception of a few blips, the market was 10%+ below its peak for about 28 months and 20%+ below its peak for about 112 months. Eleven and a half years is an awful long time to live in austerity!

I can see the similarities with guardrails and dynamic withdrawal strategies. It would be interesting to see some simulations of how well these perform and compare with the 4% rule and your variation above. But one concern I have with all of these strategies is that they typically only adjust annually. However there can be a large amount of volatility in any one year, plus the one time a year a withdrawal is made might turn out to be very bad timing (or, granted, good) to do so. Would a strategy that adjusts monthly according to inflation data and market performance allow for an even extended portfolio duration? Sort of the inverse of dollar cost averaging…

Thanks for sharing! Any idea how old Nick is and if he is retired? I love hearing about retirement from people who are actually retired because the experience is different from the math.

Very interesting article. How are the percentages calculated though? If you are just retiring on a specific date, regardless of market conditions, wouldn’t that give you a higher chance of success than people who are waiting for their wealth to reach a certain threshold? The latter group would almost always be retiring when the stock market is at an all-time high.

Very good rebut to this article from Big ERN on his blog today!!! I recommend everyone feeling like they can spend more than 4% go and read his post.

I disagree. The whole point of this post is to highlight the value of flexibility, not to optimize on the two most worst periods in history. It is not meant to be a hard and fast rule, but purely points out one of many ways to counter the unlikely event of severe drawdowns in NAV. There are many more ways to be flexible.

I would like to see a different calculation: one that optimizes for max expected years out of the office i.e. not one that optimizes for the worst sequences of return and effectively waist life in the office in the other 98% of the sequences. Such a calculation will put a greater focus on flexibility and resilience while minimizing life in the 8 to 5 office job (and effectively maximizes health)

Hey, any chance you could continue the calculation to show what a SWR would be if discretionary expenses were 100% of the withdrawal? I’m thinking about this for someone who works to cover fixed living expenses and uses portfolio for discretionary spending.

What if you delayed you withdrawal by one year and withdrew this year’s money from last years gains? You would know exactly how much money you could withdraw. You would know if you could withdraw your total 4% or if it needs to be less, or if you have some extra to leave in you nest egg. Say your nest egg is $1,000,000 and at the end of the first year you had $1,040,000 then you would know that you have the 4% to withdraw. Thoughts?

what would you do if returns were negative?

There seems to be a considerable amount of math between the article above and Big ERN but in reality personal finance is personal. My plan is to work a part time job as long as I can after FIRE which will cover all discretionary income and take less from the 4% from my investments for as long as I can.

I have always had problems with the 4% rule for two reasons.

1) It is really a worst case scenario, ensuring you have enough if you happen to retire in the worst possible year. You have a 99% chance of that not even happening. So sure it could, but probably won’t. Planning for this kind of retirement is great way to ensure you leave more money to your children than they need and leave yourself with a retirement that you could have enjoyed more.

2) The point you discuss in this article about being able to adjust your spending if your fixed needs fall below the 4% threshold which provides the ability to spend less than 4% in a bad year but then gives you the ability so enjoy yourself a bit more during good years. That has always been missing from this kind of retirement analysis.

This is the only article I have found that addresses these weaknesses in the oversimplified 4% rule. It helps in giving me comfort that I am now sure that I actually do have more than enough to retire now at 58 with absolutely no worries.

Why does the discretionary spending chart top out at 70% I was able to find it on Of Dollars and Data, but it would be nice to see it here as well. I have other income that fully sustains my lifestyle so my portfolio would be 100% discretionary and there maybe others this could help.

The main downside of this strategy seem to be that you need to have save up far more in the first place in order for it to be possible to be in a position where circa 50% of your spend is unnecessary and can be safely cut.

Meanwhile, if you can safely cut 50% of your spending without great displeasure, then one could argue why bother with that spending in the first place and proceed without it, and retire much earlier.

And if it *does* cause great displeasure to make that cut, then I don’t see how it’s an ideal strategy?

Really enjoy this article, also the 4% seems to be almost 5% these days

https://affordanything.com/560-the-father-of-the-4-rule-finally-sets-the-record-straight/

hey also found Mad Fientist there :D https://affordanything.com/555-madfientist-the-hardest-part-of-early-retirement-wasnt-the-money/

Big ERN seemed to not be a fan of this, do you have any thoughts on his stance?

Dumb question (newly FI-curious here), but do all of these withdrawal models I read about assume preservation of the original nest egg for an indefinite/infinite retirement withdrawal period (e.g. 40k annual withdrawal of 1mllion initial nest egg)? If so – they assume you die with the nest egg? Shouldn’t that be factored in somehow?

I modeled this in a spreadsheet using historical data, I used the 40 years table and 60% discretionary, so 6% (or 2.4% of starting portfolio adjusted for inflation and 3.6% of starting portfolio, not adjusted for inflation, and conditional on market conditions). The period around 1970 is still rough in that you can still run out of money several years before the end of your 40 year retirement (I guess that’s what a 98% success rate means). And that’s not just running out of money for discretionary, but also for the basic expenses.

And of course you usually die with a ton of money, if not as much as with the pure 6%

This is an interesting idea but I think a variable withdrawal driven by amortization is a better way to go.

Great article. Thanks. I just came to it. I’m in my early 60s. Basically FI but my husband still works as he loves his job.

This method effectively cuts the sequence of return risk. It also theoretically saves you from having to have a huge emergency fund to prevent yourself from having to sell in a down market.

What I would do personally is withdraw my discretionary funds every year and anything left over would go into a separate fund ring fenced for lean years.

One other not quite related issue. It would be good if there was modelling done around these rules that allowed for leaving a set inheritance for your kids. That is on my mind. I think it is incredibly hard for them to get into their own house with the money printing that has gone on. Giving them a hand up or leaving them a large sum of money is not spoiling them IMHO, it’s just the reality of the situation. I read Bill Perkins book and from then on have been helping my two twenty somethings a lot more financially than I planned to.