One of my favorite financial writers, Morgan Housel, is on the Financial Independence Podcast today!

I’m not the one conducting the interview this time though (all is explained in the episode).

Morgan’s insight into how to handle uncertainty, market crashes, and this weird stock boom that we now find ourselves in is invaluable so hope you enjoy it!

Big thanks to Gouri, Morgan, and the Bogleheads for making this happen!

Listen Now

- Listen on Spotify or Apple Podcasts

- Download MP3 by right-clicking here

Highlights

- Investing lessons from COVID-19

- Impact of the US presidential election on stocks

- Why you should plan on the world breaking every ~10 years

- The most important financial skill and why it’s important

- How to deal with greed and fear

- What you can do to get better with money

- How to use other fields to learn about investing (and the best historical period to learn from)

Show Links

Full Transcript

Mad Fientist: Hey, what’s up, everybody? Welcome to the Financial Independence Podcast, the podcast where I get inside the brains of some of the best and brightest in personal finance to find out how they achieved financial independence.

Today’s episode is actually a bit of a surprise. I just realized I was going to publish this a few days ago. And I’ll tell you a bit of the back story behind it.

Way back in 2015, I met a guy named Gouri at Camp Mustache in the Pacific Northwest. We’ve kept in touch over the years because he’s been kind enough to send me interesting articles when he comes across them. And we’ve talked about finances and things like that. And we’ve actually met up in Edinburgh when he was here visiting.

Anyway, I’ve got an email from a few days ago. And he had mentioned that he had interviewed Morgan Housel for a Bogleheads meeting. And I have been a big fan of Morgan for at least a couple of years now. I think Mr. 1500 from 1500days.com introduced me to him and said, “You have to read this guy because he’s one of the best Finance Redditors that I know of.” And I followed him ever since. And Mr. 1500 was right! He’s an incredible writer. He has a lot of great insights into financial topics, and even more importantly, human behavior topics and how they relate to finances.

So, Gouri had interviewed him for a meeting of the New York City Bogleheads Group. And he shared it with me and said that he’d be happy to introduce me if I wanted to get him on the podcast. And I listened to that interview that Gouri did… and it was fantastic! And I, of course, wanted to get Morgan on the show because I’ve been a big fan as I said. But when I listen to Gouri’s interview, I thought that his questions were exactly what I would want to ask him.

So, rather than just take another hour of Morgan’s time, I just asked if it would be okay to publish that interview on my podcast because it wasn’t going to be widely distributed anyway. And I think it’s really a valuable conversation that I want all of you to hear.

So thankfully, both Morgan and Gouri agreed. So that’s what I’m sharing with you today.

So, since the recording just kicks off with a question from Gouri, I’ll give you a bit of an introduction to everyone you’re going to be hearing today. Like I already mentioned, Gouri is a member of the New York City Bogleheads Group. And if you’re not familiar with Bogleheads, it’s a group of investors who adhere to Jack Bogle’s investing style of index funds and most of the things that we talk about on Mad Fientist actually.

Bogleheads has a forum. And if you’re interested in checking that out, I highly recommend it. It’s Bogleheads.org. And I’ll put a link in the show notes.

But Gouri is a member of the New York City Bogleheads. And he had reached out to Morgan to bring him to one of their virtual meetings.

And if you’re not familiar with Morgan Housel… he’s a writer that currently writes over at CollaborativeFund.com. And I will link to his blog in the show notes. But like I said before, he’s one of my favorite financial writers. And he just released a book called “The Psychology of Money,” which I’m extremely excited to read—I haven’t yet. And the reason for that is because I haven’t got it early. It just got released.

So usually, when I interview authors around a book release, the publisher will get in touch and send me an advanced copy. But since I didn’t actually interview Morgan, that didn’t happen. So I’m excited to read it just along with everybody else in the general public. But since it was just released, I haven’t done it yet. So I can’t really speak about the book, but it sounds excellent. And just like all of Morgan’s writing on finances, I am really looking forward to reading it.

So, I will put a link in the show notes to that as well, if you want to check that out.

Anyway, as for me, I am excited to introduce these two guys. And apologies for the audio quality. It sounds like Morgan was just calling in from his cell phone or something. And obviously, I wasn’t anticipating this to end up as a podcast. So apologies for not having the normal audio quality that you’re used to. But the discussion is interesting enough that I definitely think it’s worth it.

So, big thanks again to Morgan and Gouri for letting me do this and to the Bogleheads for letting me share their meeting presentation. And I hope you enjoy it as much as I did.

Gouri: How has CoVID challenged, affirmed and changed your beliefs, and are there new realizations and practices for you?

Morgan Housel: So, two things come to mind here: one is, something I’ve always believed, it just gets so driven home this year, is that the biggest risk in any year, in any era, and I think in almost any field, the biggest risk is always what no one is talking about.

So, we always, as investors, as people thinking about money, think about what is the biggest risk over the next year, the next ten years. And there are events that we can think about. There’s the coming election, there’s trade wars, there’s stimulus deals, CoVID-19, when are we going to get a vaccine… all these different things that we know and we can talk about. But in any given year, it’s always the case. And I truly mean it’s always the case. In any given year, the most important story in finance is something that no one could have possibly been talking about before it happened—whether that was CoVID-19 this year.

You know, people have been talking about pandemics for a long time—Bill Gates gave a TED Talk in 2015 warning about basically this exact event. But the timing and the magnitude of COVID-19 is not something that anyone could have known before it happened.

The same is, of course, true for September 11th, Pearl Harbor, the Great Depression, JFK being assassinated… all these big, huge, monumental events that really moved the needle, when you look back, you could say, “That event is all that matters.” So to speak, those events are always the one that you could not see coming.

And that fact that you couldn’t see them coming is what makes them different. It’s what makes them dangerous.

People are very good at preparing for known risks, preparing both financially and psychologically. People care financially, getting their cash flow in order, so to speak, but they prepare psychologically, so that when it comes, even if it’s a big event, it’s not shocking. It’s not jarring to them.

It’s very different for something like CoVID where, for the United States at least, it seems like there was about a three- or four-day period in early March where everyone doubt it. And very quickly, what seems like virtually overnight, businesses shut down, schools shut down, airports ground to a halt. It was such a shocking event that you can really distinguish—you know, pre-March and post-March were very different worlds.

That was the case for September 11th. We refer to it by the date because everything changed in one day. The world, September 10th, was very different from September 12th. Everything changed that day.

So, that’s always the case. And that’s been re-affirmed this year. And of course, it’s going to be the case going forward. People are more attuned to financial and economic risk right now than they have been in a very long time. So, more people than ever are looking ahead saying, “What’s going to happen next? What are the biggest economic risks for the rest of the year? What are the biggest CoVID risks?” without realizing that we learned this year is that the world is surprising. And the biggest event, the most monumental stuff that moves the needle is always going to be surprising.

So, the biggest risk for the next year, it’s something you and I and everyone else cannot be talking about right now because, by definition, we don’t know about it.

Gouri: So, building on that, to what extent, broadly speaking, not necessarily limited to this year and this election, but including this election, to what extent do you think politics matter? And any comment on this upcoming election?

Morgan: I think this was about 2010. I was at a conference, and I was listening to a banking lobbyist give a talk. And it was a really good talk. And he had been involved in presidential elections for, I think, 30 years at that point. And he made this quip that every single election that he had ever been involved with over those 30 years, every single election, people said, “This is the most important election of our lifetime.” And he made a joke that like, look at some point, it’s not. At some point, it’s not the most important election of our lives. It’s just this normal path of history.

Of course, in 2016, I used that example prior to the election of saying, “Look, this truly is the most important election of our lifetime.” That’s what it felt like in 2016. And now, I would say it again in 2020… this is the most important election of our lifetime. It always feels that way even if you say it every single time.

On one hand, the long history of one party saying, “If the other party wins, the whole country is going to collapse,” is really wrong. We can see—of course, not universally—Franklin Roosevelt is, by and large, by historians, viewed as one of the great presidents of our time. I know it’s a controversial statement. But in general, among historians, it tends to be true. He was so incredibly controversial at the time, particularly in 1932 when he was elected. The number of people who really thought that this was going to usher in an era of communism or fascism that was sweeping over Europe at the time was very, very high.

So, there’s a long history of people saying, “If this guy wins, then all bets are off! The country’s going to collapse.” There’s a long tradition of that.

There’s also a long tradition of investors saying, “If this party wins on either side, then buy these stocks. Well, here’s what the stock market is going to do next.” And those series of predictions that they tend to have, the worst track record of any group of economic predictions.

I mean, just the recent examples… when George W. Bush won in 2000, a very common narrative that made a lot of sense was Bush was going to deregulate the banks—so buy the bank stocks, and he’s going to have a tax cut, which is going to be good for travel, so buy the airline stocks. And I’m not making fun of that narrative because it made sense at the time. That’s a reasonable narrative to make.

Of course, by 2008, most of the airlines were bankrupt. And most of the banks were bankrupt as well. It turned out to be the worst investing situations you could have.

In 2008, when Barack Obama was elected, a common narrative was buy the solar companies because there’s going to be a big push for green energy. And of course, within years, most of the solar companies themselves were bankrupt. It turned out to be one of the worst trades that you can make.

A lot of people in 2016, there was this general idea that if Donald Trump wins, then terrible for the economy, terrible for Trump, for whatever reason that will be, terrible for the stock market. And the stock market […] since then.

It’s so easy to look back at these reasonable narratives that makes sense that turned out being the exact opposite, which I think is just the case that people tend to give the president on either side, on either party, more credit and more blame than they generally deserve.

Now, it’s not to say that the president is not powerful. But in the list of variables that matter in the stock market and in the economy, they’re lower down on that list than most people would think.

So there are other variables that matter a lot more.

Of course, I have my political beliefs—strong, political beliefs. I have my views about where I really want this election to go. But none of those affect how I manage money… yet, at least, I would say.

I think one of those dangerous things that investors can do is when they have very strong political beliefs—like a lot of us do—but they let those political beliefs guide how they invest particularly in the short term. That’s when things get really dangerous. I think there are few poisons to the investing process more potent than really strong political beliefs that you mix with your investing decisions.

Gouri: So we might consider doing the opposite of whatever the pundit say.

Morgan: If you have to make a bet, historically, that would be the better bet. The mind for most people is, if you are happy with your investing portfolio right now in September, you should be happy with it in the middle of November regardless of who wins. And if on November 4th, whatever the day after the election is, if you are trying to make huge changes to your portfolios, and you consider yourself to be a long-term investor, and you still want to make big changes to your portfolio on November 4—not to me, not for everyone, but in general—it’s increasing the odds that you’re going to make a regrettable decision down the road.

There’s so much history that goes against doing that and so much reason to believe that strong, political beliefs that influence your investing decisions just so often turn out wrong and regrettable. And to me, if you are a long-term investor, that means you are a long-term optimist. Now, I want to be investing for the next 20, or 30, or 40, or even 50 years. And therefore, what’s going to happen in the politics in the next four or eight years, by and large, is not going to have a tremendous impact on that.

Of course, you can think of situations where, because of any single president or congress or whatever it is, there is some sort of political catastrophe. There’s history of that—not just in the United States, but across the world. So it’s not black and white. But to me, the odds that I just want to let things compound in the next 30 years and not make short-term decisions based off who wins the elections are pretty overwhelming.

Gouri: Excellent! So you’re known for reading a ton of both current events and commentary as well as history. How do you separate signal from noise? And how do you, not just for reliable, existing sources, but signal from noise for new sources and opinions that differ?

Morgan: The first thing I would say is I don’t pretend like I’m any good at it or any better than anyone else. Everyone wants to separate the signal from the noise, but we are creatures of looking up confirmation bias, and looking for things particularly when we’re talking about history examples and little nuggets that concern what we want to believe, the view of the world that we want to have.

So, I won’t pretend like I or anyone can do well at that. But to me, the biggest thing with history is, there’s so much to learn from history, but most of what we want to learn are not the specific event. What we want to learn about, by and large, are the really broad events that teach you how to people think about behavior. And the really big, recurring events that tend to show up at multiple different parts of history, that’s what you should pay the most attention to.

Jason Zweig of the Wall Street Journal had this great idea. Why do people keep making so many financial blunders? Why do we go from bubble to bubble? Why can’t people learn their lesson, so to speak? And his idea is it’s not that people don’t learn their lesson, it’s that people learn too precise a lesson.

So, in 2000/2001, the lesson that people learned was “don’t buy expensive [TEX] stocks.” They learned a really precise lesson. They didn’t necessarily learn about boom and bust. They just learned this very precise lesson about dot-com [TEX] box. So a lot of those people moved towards Miami condos. And then when that blew up, the precise lesson that they learned was don’t buy Miami condos. And then, they moved on to bitcoin or gold or whatever it was.

So, they learn these very precise lessons without the really broad takeaway that has to do with human behavior.

So, when I look at history, it’s not poring over data and looking for correlation about when GDP does X, the stock market does Y. That’s one version of looking at history. But for me, I’m much more interested in the really broad takeaways about how people deal with greed and fear and what-not.

And to me, like some of the takeaways that are important to me are a) this idea that the world breaks every five to ten years. And if you go back historically, there’s almost no exceptions to that. But every five or ten years, not exactly on that time scale, but roughly about that on average, something happens in the world where everything grinds to a halt and a lot of the assumptions that people had about how the world works break.

So, we’re dealing with one right now with CoVID-19, but there is also the financial crisis of 2008, September 11th, the dot-com explosion, the fall of the Soviet Union, the inflation of the 1970s and ‘80s, JFK being assassinated, the racial tensions in the 1960s, the Great Depression, World War II. It goes on and on and on.

There is never a period where you can go five or ten years of calm. The world is constantly breaking. And that’s really important as an investor because, once you expect that to happen as just the normal course of events, even during a period where things do really well—

The stock market has done extraordinarily well over the past 60 years. So you’re betting on long-term optimism. But if you spend much time in history, you have to be a short-term pessimist because there is no period in history that avoids short-term pessimism. Pessimism is that constant, never-ending chain of bad news.

So, if you have that as a mindset, that long-term optimism is possible even if there’s constant, never-ending chain of short-term pessimism, then it helps you get through the short-term problem, the short-term breakages. And if something like CoVID-19 occurs, to me, it is shocking, I didn’t expect it, it’s brutal, it was scary, it still is scary, but I think it’s a little bit easier to deal with particularly as an investor if you realize that, over the long course of history, this is the kind of thing that happens even in the mid- to backdrop of a really extraordinary long-term growth.

It’s not intuitive to think that the world can break every five or ten years. Even during a period where, the last 50 years, the stock market has increased 200-fold, it’s not intuitive… to think. We either have those many problems, those many setbacks, deep, really, structural problems during a period where you have extraordinary growth that you can take advantage of. It’s not intuitive, but that’s how history works over time.

So, I think those kinds of really broad behaviors, those broad takeaways about behaviors, are what people should take away from history, rather than the specific events and learning too precise a lesson from what’s happened in the past.

Gouri: So switching to you personally for a few minutes, you’ve mentioned that you’re working towards financial independence. I’m curious… I know you clearly love your work. You’re really good at it. You chose it. You honed your skills. How do you envision financial independence? What would you do more of or less of? And what would you give up and what would you really take on?

Morgan: I think there’s a spectrum of financial independence, obviously. It’s not necessarily black and white. There’s that one level where if you just have a little bit of savings, you’re a little bit more independent than you were versus someone who is just solely relying on the kindness of strangers. If you are good at your job, that’s a level of independence. So there’s a big spectrum of it.

To me, the level that really matters is when you can, for various reasons, just wake up and virtually, any day, say, “I can do whatever I want today.” You can work really hard at a work that you’re really passionate about if you want to do that. But if you wanted to take time off, you can do that too. You want to hang out with your family, you can do that too. It’s just maintaining control over your schedule.

And there’s a lot of different ways to do that. That roughly falls into the FIRE framework—financial independence retire early—which is something that I like in the sense of financial independence. But “retire early” is almost this idea that you are committing yourself to not working again, which is where it gets a little rough for me because, most people, even if they have full control over what they do, most able-bodied, smart people who are underage 65 would say are going to wake up most days and say, “I want to do good work today. I want to go to work. I want to put my brain to work, put my muscles to work and be productive in society.” That’s what most people want to do.

But I think just as long as you can do that on your own terms, doing the projects that you like, when you want to do them, who you want to do them with, for as long as you want to do them with, and then you can stop whenever you want, that to me is the highest dividend that money paid.

And it’s really important because a lot of financial material stuff, which is not—this is where people get accustomed to it over time. It’s not that a fancy car or a nice house is not going to make you happy, but you tend to get accustomed to it, whereas controlling your time is something that gives most people an enduring level of happiness. And every day that you can wake up every morning and say, “I can do whatever I want today. I can go to work, but I could quit. I can retire. I can do something else,” every day that you have that is going to give you a lasting level of happiness that it’s hard to get used to over time. It tends to be enduring over time.

And the opposite of that—waking up every morning and realizing that you are on someone else’s schedule, that someone is going to tell you when to go to work, where to go to work, what to do at work, when you can eat lunch, when you can go home, that tends to be just a level of dependence on other people that brings a lasting level of angst and unhappiness and stress.

So, that’s all I care about with financial independence, is that my career moves more towards this idea where I can do whatever I want. And what I want to do is write—which is what I’ve always done for work. As long as I can move and move toward this idea of “Look, I’m going to write when I want to. I’m going to write about whenever I want to. I’m going to do it for as long as I want to. I’m going to publish it where I want to,” that to me is what really matters in terms of financial independence. But I’m always going to keep writing because it’s what I love to do and what I’m passionate about.

Gouri: Excellent, excellent! How did your childhood and your parents influence your current work?

Morgan: So, I wrote about this in the book. My father started his career later. He started his undergraduate college when he was 30 and had three kids. I’m the youngest of three. So, he started his undergraduate college a few months after I was born. And he became a doctor. He became an MD when I was in fourth grade or something like that.

So, he started really late. And that was important because, in my early childhood, the time I was born through, let’s call it fourth grade, we were very, very poor. So my parents were students. We were living off of grants and student loans and we had no money. We had nothing. So I got to see that side.

Of course, when you’re young and you haven’t experienced anything else, you don’t know that you’re poor. I had a great childhood. I liked playing with my parents and playing in the backyard. And we went camping. But you don’t know what you’re missing.

But then my father became a doctor when I was in fourth grade. And we moved on to a much more comfortable way of living. He had a doctor’s salary and that was what we had. We bought a nicer house. We went on vacations. There was a very stark change that happened when he became a doctor, as you can imagine.

But what was really important for them is that the forced frugality that my parents had when they were students, trying to raise three kids off of grants and student loans, that forced frugality stuck with them even after their incomes rose, after my father became a doctor.

So, even as a doctor, we lived a more comfortable life, but they were very frugal, and their savings rate was very high. And what that led them to after 25 years of working was my dad basically woke up one day and said, “I don’t want to work anymore. I’m ready to retire. I’m ready to move on.” And he just did.

And he was able to do that. He had that level of independence because he had a high savings rate from his old career that let him do that.

So, that had a big influence on me just like in the last five or ten years. It didn’t really hit me until that event occurred in the last decade that, wow, that was something really important, that this frugality that’s stuck with them for his whole life gave him this decision, led him to make this decision on his own terms whenever he wanted to in a way that was so meaningful and important in life that I wanted to do that.

So, growing up with that level of frugality just as the base case for me stuck with me. And I don’t necessarily consider myself frugal because I buy whatever I want, but my wants and desires aren’t that great. They’re not that high.

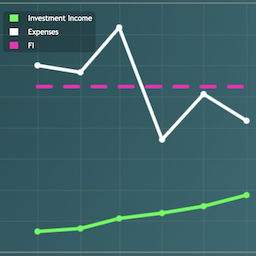

I think one of the most important financial skills for anyone is getting the goalpost to stop moving. It’s the most important. It’s probably the hardest financial skill. It’s when you get more income, either from your work or from investing returns or inheritance, whatever it is, that your material aspirations either don’t grow or they grow slower than whatever that income jump is. That’s the only way to build wealth over time. That’s the only way to get any sort of satisfaction over a growing money that you have, is to get the goalpost to stop moving.

So, I don’t consider myself necessarily frugal, but I think my wife and I have done an okay job at getting the goalpost to not move that much, so that as incomes rise, we feel like we’re actually getting something out of it.

And this is important because so many people don’t do that or they do the opposite. The goalpost is moving faster than their incomes. Their aspirations and their expectations are moving faster than their incomes. So even if their incomes are rising, and they become a doctor or a dentist or an investment banker or a lawyer, whatever it is, their income may have gone up 5x, but if their expectations jump 6x, it’s a really simple equation at that point.

So, keeping your expectations low in a way that gives you control over your life, control over your time, control over your freedom, it’s something that I took away from my parents that was really meaningful for me.

Gouri: So, frugality is obviously was a huge thing to Jack Bogle. It’s obviously important to a lot of Bogleheads. And like you said, it doesn’t mean scrounging on everything or denying yourself of basic things. I think it’s a misunderstood term.

But can you comment more broadly—you’ve used this phrase, “Wealth is what you don’t see.” Can you elaborate on that?

Morgan: So, wealth is what you don’t see because what wealth is money that you haven’t spent. It’s money that you’ve saved and you have invested. It’s the stuff that you haven’t spent. It’s the stuff that we don’t see because no one sees other people’s bank accounts or their brokerage statement. All we see in the world is what people have spent—which is really the opposite of their wealth. We see the cars that they’re driving, and the homes that they’ve purchased. That’s what we see. That’s what’s visible.

But no one’s get to see what your brokerage account statement is. It’s invisible. And that’s a really big deal because it really impacts how and who we learn from.

I’ve used this example of, in health, in fitness. You can see someone who is in really good shape, someone who is very physically fit. And maybe it’s subconscious, but you tend to think, “Wow, it would be great if I could look like that too. I want to look like that.” So that’s my inspiration, my motivation, to go to the gym because I want to look like that person. Even if it’s subconscious, that tends to be what people think.

But with wealth, we can’t really do that same thing because the people who are very wealthy, we don’t see their wealth in the same way that you can see someone’s biceps.

Since wealth is invisible, we tend to look at the people who have spent money, and they tend to be who we admire. Those tend to be the people who say, “Oh well, that person is driving a Lamborghini. They must be really successful. So I should aspire to be them.” But a lot of people who are driving Lamborghinis and living in big homes are not wealthy because they have spent the money that they have. That’s why they have so many nice toys.

Think someone like Warren Buffet. His net worth is public. We know what his net worth is. It’s reported everywhere. He’s worth about $80 or $90 billion. It’s very public. There’s no secret. But if we did not know that, if we were just looking at Buffet the man, he would be no one’s financial role model because he wears cheap clothes, and he drives a mid-level Cadillac and lived in the same house that he bought when he was 25.

So, what is visible from Buffet is nothing. You don’t see the wealth at all unless you have this inside information about him that is now public about what his net worth is.

So that’s where it gets really difficult just in terms of who we admire, who we look up to, who we seek inspiration from when wealth is invisible.

I write about some people in the book who have extremely humble backgrounds and were secretaries and janitors who went on to achieve tremendous financial success. But people didn’t learn about it until they died because there was nothing visible for you to see. The only way that you’re going to learn about their financial success is when they died and their estate was opened up, they left a lot of money to charity. That’s the only time that it was visible.

So, all these people who are no one’s financial role model when they were living become people’s financial role models after they die and things open up. So it’s just this irony.

I’ve always said, particularly, for young men, when a lot of people say that want to be a millionaire, what they actually mean is, “I want to spend a million dollars.” And that’s literally the opposite of being a millionaire. There are lot of ironies like that in finance that are just hard to wrap your head around. The idea that wealth is what you don’t see just changes your perspective on what you see in the world and who we look up to.

Gouri: So going back to Bogleheads, a lot of even Bogleheads or stay the course hands-off investors are asking, “My portfolio is in all-time high right now. I understand timing the market is unlikely to be executed well,” they want to take some cash out… what do you say to those folks who are familiar with the fundamentals?

Morgan: I think there are two things to think about here. One is that if you’re just taking a re-balancing approach, and it’s an annual re-balance or quarterly, or even if you’re talking about re-balancing once in every five years, that is I think not just okay, but a smart thing to do. And as markets have done really well, if you were to re-balance right now, you would almost certainly be selling stocks and putting more in the cash and bonds. So, that from that perspective, it makes a lot of sense.

If it is not a re-balancing, if it just this one-off, “Hey, the market’s gone up a lot during this pandemic. It makes me nervous, and so I want to sell,” I think that’s a slightly different thing. But it’s a really important distinction. If you are a long-term investor, even just for the next ten years, which to me is the shortest long-term time period, we know with a certainty that the market at some point in the next ten years is going to decline 20% or 30%. We don’t know when it’s going to occur. We don’t know from what levels, but that level of volatility occurs in every ten-year period looking historically.

So, we know it’s going to happen over the next 10-year period. So, if you know that it’s going to happen, and that it doesn’t necessarily preclude long-term growth, that a decline of 20% or 30% or even 50% is normal during a period when the market does very well over a longer period of time, then my question would be, “Why are you trying to avoid it? Why are you trying to avoid something that might not happen? You don’t know when it’s going to happen. There might be serious tax consequences for doing it. Why would you try to avoid it rather than just setting up your mindset to endure it over time?”

It’s not fun to deal with watching a third of your money disappear like we all did in March. Not that it’s fun, it’s not that it’s enjoyable. But I think if you have a deeper understanding of market history, those kinds of things are actually pretty normal. Even if it’s in the backdrop of long-term growth, then it gets easier to just say, “I’m just going to accept it.”

So look, I’m a hands-off investor. But I’m really interested in economic cycles and valuation cycles, et cetera. I’m really interested in that. So if you would ask me today, “Is the market expensive? Are we due for a pullback?”, I would say, yeah, probably. Both of those things are true. So what am I doing about it with my money? Nothing. I’m not doing anything about it with my money. I understand that both of those things should probably temper my expectations over the next ten years of what’s possible. It should increase the idea of a major sell-off at some point in the next couple of years. But I don’t know when it’s going to occur. I don’t know why it’s going to occur or from what level. And I’m confident that, whenever it occurs, it will eventually recover in due time.

And this year, in 2020, the recovery happened in 60 days. Much of the decline, 35% in March, and we’re back at all-time high now.

So that’s the other thing about it is that if you sell, if you make this decision to get out now because things are crazy, you better be damn sure that you have a plan to get back in on time.

And when is that “on time” going to be? No one in their right mind, if you go back to March, when the economy was falling apart and tens of millions of people were losing their jobs with $3 trillion stimulus package and truly looks by reasonable statistics that we are heading into the second great depression, no one back then would have said, “The S&P 500 is going to be at all-time high’s by August. And by the way, Tesla is going to be at 800% during this period” No one would have thought that.

So, when the rebound is just as unknown as the decline, it should give you a little bit of humility about thinking ahead of, “Okay, if I sell now, when am I going to get back in? Am I ever going to get back in? Do I want to get back in?” because obviously the behavior that you want to avoid is the classic selling during fearful periods and buying during doom periods.

So, if your idea is you’re going to sell now after the collapse, and then when the market rebounds, again, you’re going to get back in… well, that’s almost certainly going to do traction in the long-term returns versus just enduring it over time that would’ve left you off in a better situation.

Gouri: A lot of folks in this crowd understand that it’s a few huge companies that are pulling up the market. So I think the broader public sees the market is doing really well. Can you talk about the seeming disconnect between economic chaos, societal uncertainty, market doing well, but a lot of other companies aren’t?

Morgan: I think it really comes down to two things. One is that is if you look at the S&P 500 companies, just five companies—Amazon, Google, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft—just those five are more than a quarter of the index right now. And those five companies are doing extraordinarily well from the business sense. Revenue profits were doing—they’re not just holding up, they’re doing phenomenal right now.

So, since they are a disproportionate of the market, and those five companies have driven a huge share of overall game this year, that’s where you get the disconnect.

Whereas if you are looking at small-cap value index, a lot of those companies are doing very, very poorly as you would expect to happen during a recession or depression that we’re dealing with right now. That’s one of the disconnects of why so many small business, particularly, just mom-and-pop restaurants and drycleaners on Main Street are just absolutely struggling right now when the NASDAQ is surging to all-time high’s. That’s part of the disconnect.

Another part of the disconnect is Federal Reserve policy. There’s definitely trillions of dollars in liquidity into the economy with the sole express intention of driving up asset prices. That’s not a side effect. That is the intention of what they are doing. So, whenever you have someone with literally—not virtually, but really, an unlimited supply of money that is willing to do anything to prop up asset prices, those in bond and equity markets, of course, that’s what’s going to occur.

I say that in hindsight. If you go back to March, I wouldn’t have expected it this quickly. But it does make a lot of sense when the Federal Reserve has been as aggressive as it has that you’ll see something like this.

And the Federal Reserve, their orders of operation, what they’re willing to do, has dramatically changed in the last ten years. If you go back to 2008, Ben Bernake was viciously criticized for cutting interest rates from, at the time, 4% to 2%, if you go back to 2007 or 2008. People thought he was being reckless, that this was going to lead to hyper-inflation, just for cutting interest rates versus today, in 2020, the Federal Reserve is literally buying corporate bond […] It’s a completely different degree in what the Fed is willing to do just in the last 10 or 12 years.

So, of course… are there going to be consequences, risks of that? Of course, absolutely. But we also shouldn’t be surprised necessarily that what is happening in asset markets, both in stocks and in bond markets across the world is happening amidst this backdrop of what the Fed is doing.

Those to me probably explain the majority of what’s going on in the stock market. But there’s also these unknown situations. Retail investing has surged as a share of stock market activity. Robin Hood and other brokerages has absolutely exploded in the last four or five months. Some people attribute that to be there’s no more sports betting. There’s no more sports to watch, so people are now day trading Netflix […] Is that at least part of what’s going on? I’m sure that is part of it.

There’s always other variables that go into it. So it’s never black and white where we can say “the market is [thriving] because of X.”

But those are the explanations that I think make most sense to me about trying to make some sense of the disconnect between 40-million people losing their jobs and stocks are at an all-time high this summer.

Gouri: Going back to the behavioral side of things, you’ve mentioned that 10% of people are born savers and investors (they have this inherent discipline), and that at the other end of the spectrum, there’s 10% of people who have stronger tendencies to trade or just be the opposite of those natural savers and investors with 80% roughly in between those two.

What have you seen helped people transition into that saver and investor group?

Morgan: I don’t know. And first of all, the numbers where I say where 10% of people don’t need help, 10% of people can’t be helped, 80% of people want and need good advice, I’m making those numbers up, but it feels like its directionally accurate for me.

I’m actually not sure that a lot of people move from one group to another. I think that the 10% or so of people that I’m guessing who can never be helped are always going to be compulsive gamblers, always spending more than they have, always driving themselves into debt. I think there’s a group of people for whom you just can’t do anything for. And that’s just the way it is.

We’re never going to get to a point where everyone in society is good with money no matter how much information or how much education we have out there. There’s always going to be a pretty good subset of people that are just running themselves off a cliff, so to speak.

And to me, the target for financial advisers should be the 80% in the middle who want and need good advice. And I think for those people, it really comes down to good communication about talking about market—well, two things: the history of markets, particularly, market vitality, and how common vitality is, and understanding what causes it and how it passes, and again, how it does not conclude long-term returns, long-term growth—that’s important—and becoming introspective with yourself or working with your clients to understand your own risk tolerances, your own goals, what you want out of investing, what is important to you, and also, your flaws—what you are not good at, where you tend to have a poor relation with greed and fear, those kinds of things.

Everyone, no matter who they are, is susceptible to the force of greed and fear. It’s not that you can control that. But to the extent that you can remove that from your decision-making process, the better.

And look, […] index funds. I don’t do anything else. I don’t sell. I don’t make any larger purchases. I just stick to a clean strategy. But I am not, in anyway, immune to greed or fear.

I was really worried in March. I didn’t make any changes to my investments, but I was worried. I was worried about the economy. And on the flipside of that, when stocks were in all-time high, it feels great. And I’m probably subject to the wealth effect. So, I’m not saying that myself or anyone is immune to that. And I think people who are thinking they are immune to that are probably kidding themselves. But if you can just make sure—it’s fine to be greedy and fearful as long as you don’t mix that with the decisions that you make.

So, as soon as you start saying, “Oh, I’m greedy, so I’m going to buy more. I’m fearful, so I’m going to sell everything,” that’s when things start to blow up.

And that’s really important because a lot of people, when they’re thinking about behavioral finance, will ask a broad question more or less like, “How can I stop being so greedy or fearful?” My answer is you can’t. You cannot learn about something, reading a book or learning a new formula, that is going to counter cortisol and dopamine in your brain. It’s never going to happen. It’s just an integral part of who you are.

So, rather than thinking that you can fix it and get around it, I think you would have to situate your finances in a way that embraces it and just make sure that even if those emotions are there, that emotionalism that is making you change your decisions or leading to new decisions is what you’re actually trying to manage rather than trying to get rid of those feelings altogether.

If you get those two things down—understanding market history and understanding yourself and your own goals, that to me is 80% or 90% of what matters in terms of managing money. That’s what’s really important for people.

Gouri: So, building on that, you’ve mentioned there’s a thin line between bold and reckless. So obviously, investors have a mantra that higher return requires higher risks. So boldness is often rewarded. Can you elaborate on that thin line between the two?

Morgan: In both business and investing, it gets dangerous when we admire and look up to people who have been very successful because, lots of times, the behaviors and the decisions that were necessary for extremely good returns or be of high success are the same behaviors that would have led to a disaster in terms of a huge decline. So it’s both swinging from the fences.

And risk and luck, I think, are more or less the same thing. There’s just opposite sides of the same coin. They are both the idea that there are things that can happen in the world that are outside of our control, but have a big impact, a big influence on outcomes.

So, risk and investing, we understand what that is. There are things that can happen that are outside of our control in the stock market, in the economy, where we can try to make a good decision, where the odds are in our favor, but we just end up on the unfortunate side of the odds. We know that’s the case.

Luck is the exact same thing. Whereas luck is things that happen in business, in the economy that are outside of our control that have a bigger impact on outcomes and anything we intentionally did.

The disconnect where it gets dangerous is that people are keenly aware of risk in investing, they adjust the returns for risk, they hire risk managers. But luck is very different. Even though we know luck is out there, we know it’s virtually the same thing as risk, it’s just the opposite, but we don’t tend to talk about luck like we talk about risk. It is rude to accuse another investor or a successful businessperson of being lucky. You just look like a jerk if you’re doing that. If you say, “Oh, this hedge fund manager is a billionaire, but they’ve just been lucky,” it just makes you look cynical or bitter.

And for yourself, it hurts to look yourself in the mirror and say, “All of the success that I had, or at least the big portion of it, is just due to luck. I didn’t really do anything.” That’s a hard thing to accept.

So, even though we know luck is a powerful force in the world in business investing, it’s much more difficult to talk about it and think about it than risk is.

And that’s why it gets dangerous to look at really successful businesspeople and say, for example, what did Jeff Bezos do and what can I do that he did that that’s going to leave me as an entrepreneur with the kind of success he has? Well, there are so many different areas of luck that led to Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk or Bill Gates that led to their success. And that does not mean that they were not skilled or hardworking. It doesn’t mean of those things. Of course, they are skilled, and smart, and hardworking. But there’s a level of luck in there that is impossible to emulate on any consistent basis.

I talk about, in the book, one example of this. Bill Gates went to the only high school in America that had a computer. So if you think about the ark of Bill Gates’ life… is he smart? Is he hardworking? Oh, my gosh, yes, He’s one of the smartest, hardest working, insightful, forward-looking business leaders that we’ve had in a century.

But is he lucky? Is at least a major part of his success due to luck? Of course, due to being in only the high school in America with a computer that set him on this path to where he got to now. And that was the decision that he didn’t put any thought into. I don’t even think his parents put a lot of thought into, that they were going to send Bill to this private school because they have a computer. It was a serendipity luck that led to that.

And the more we acknowledge and accept that that is a major part of how business and investing works, the more humility that you have in terms of learning from other people and back towards learning from history. It pushes you away from really precise lessons from other investors or other businesses and more toward the big, broad patterns that tend to show up in lots of areas in business and investing.

So, it’s just a push towards more humble way of learning about the world.

Gouri: Excellent! So, the next question I want to ask, I’ll call it a loophole question so folks know many of the short-term, enjoyable things, that things with immediate gratification, have a long-term negative cost versus the opposite things with long-term reward have this upfront unenjoyable cost… but there are things that are enjoyable near-term that are also good for you long-term. So, I jokingly say, for me, that’s guacamole. I love it and it’s good for you.

And for a lot of people, it’s exercise or saving and investing. What have you found marries the two, enjoy it now, and it’s also good for you long-term?

Morgan: The one that comes to mind the most for me is writing. I always joke like, please don’t my bosses, but no one needs to pay me to do this. I really enjoy doing it. I love the process of learning about how the world works and trying to find a story and trying to tie it back to finance. I love doing that. That’s what comes to mind most for me. And I’ve built a career out of doing it. So that’s a long-term payoff. But that to me is what comes to mind.

And that actually goes back to what we’re just talking about luck. How I got into writing and how I became a writer was not planned at all. It was truly just dumb luck of just stumbling across an opportunity that I had never planned for, and it just happened to work out.

But I think that’s true for a lot of people. I think the main driver of what’s going to make most people happy is the combination of their marriages, their mates, their spouses and their career. Those two things are the overlying majority of what you’re going to be dealing with on a day-to-day basis. So, if you get those two things right, then not a lot of other things can really get in the way that’s going to tear you off track. If you get those two things wrong, there’s not a lot you can do that’s going to set you on the right track.

And a lot of that for myself, I’d say, my marriage too is another thing where I feel like it was just dumb luck on how it came together.

So to me, it’s those two things—it’s work that I love and happy relationship, happy friends—that leads to the most amount of instant gratification and also has a long-term payoff for me.

Gouri: Excellent, excellent. You’ve mentioned the importance of learning subjects outside of personal finance or investing. In closing, are there a few high-level categories that you’d suggest pointing people in the direction of? You mentioned history. Are there others?

Morgan: So, there are lessons that we can take away from history, in biology, in politics, in military history, all these other fields, sociology that having nothing to do with investing, but they all fall into this umbrella of how do people behave, how do people make decisions around risk, and greed, and fear and uncertainty and scarcity.

So, what I try to do in this book is use a lot of stories that have nothing to do with investing, nothing to do with finance, nothing to do with economics. But they open up a window, so to speak, in terms of how people make decisions, how people decide what they’re going to do, what people’s preferences are that have a clear investing takeaway that we can learn from.

One that’s always stuck out to me is the period in U.S. in world history was from about 1920 to 1945 which holds the boom of the 1920s, the incredible bust of the Great Depression, and then the tragedy, trauma and uncertainty of World War II. I think that learning about that period, there is no greater period in modern history where there’s a lot of historical recording in terms of just books and documentaries written about that period that you can learn how people deal with greed, fear, uncertainty, tragedy, trauma, than that period. I think it is such a window into the human condition and just how people deal with the ups and downs in life.

I’ve always been fascinated with that period just for that reason. There’s no other period in modern history where you can learn more about how humans think and behave under pressure than that time period.

So, I’m always fascinated with the Great Depression and World War II. The Great Depression, obviously, has direct investing takeaways. You wouldn’t think there would be in World War II, but there was so much—

Just think about something like innovation. World War II started on horseback and finished with nuclear fission just six years later. So much scientific innovation took place during that period that you can learn a lot about human progress and ingenuity and innovation through the lens of World War II—which is not obvious but I think if you dig into it, it’s just a really fascinating period.

Gouri: Excellent! Well, thank you again so much… really powerful, insightful, practical. We loved having you.

Morgan: Thank you so much for having me. This has been fun. I really appreciate it. Thank you.

Today’s episode is actually a bit of a surprise. I just realized I was going to publish this a few days ago. And I’ll tell you a bit of the back story behind it.

Way back in 2015, I met a guy named Gouri at Camp Mustache in the Pacific Northwest. We’ve kept in touch over the years because he’s been kind enough to send me interesting articles when he comes across them. And we’ve talked about finances and things like that. And we’ve actually met up in Edinburgh when he was here visiting.

Anyway, I’ve got an email from a few days ago. And he had mentioned that he had interviewed Morgan Housel for a Bogleheads meeting. And I have been a big fan of Morgan for at least a couple of years now. I think Mr. 1500 from 1500days.com introduced me to him and said, “You have to read this guy because he’s one of the best Finance Redditors that I know of.” And I followed him ever since. And Mr. 1500 was right! He’s an incredible writer. He has a lot of great insights into financial topics, and even more importantly, human behavior topics and how they relate to finances.

So, Gouri had interviewed him for a meeting of the New York City Bogleheads Group. And he shared it with me and said that he’d be happy to introduce me if I wanted to get him on the podcast. And I listened to that interview that Gouri did… and it was fantastic! And I, of course, wanted to get Morgan on the show because I’ve been a big fan as I said. But when I listen to Gouri’s interview, I thought that his questions were exactly what I would want to ask him.

So, rather than just take another hour of Morgan’s time, I just asked if it would be okay to publish that interview on my podcast because it wasn’t going to be widely distributed anyway. And I think it’s really a valuable conversation that I want all of you to hear.

So thankfully, both Morgan and Gouri agreed. So that’s what I’m sharing with you today.

So, since the recording just kicks off with a question from Gouri, I’ll give you a bit of an introduction to everyone you’re going to be hearing today. Like I already mentioned, Gouri is a member of the New York City Bogleheads Group. And if you’re not familiar with Bogleheads, it’s a group of investors who adhere to Jack Bogle’s investing style of index funds and most of the things that we talk about on Mad Fientist actually.

Bogleheads has a forum. And if you’re interested in checking that out, I highly recommend it. It’s Bogleheads.org. And I’ll put a link in the show notes.

But Gouri is a member of the New York City Bogleheads. And he had reached out to Morgan to bring him to one of their virtual meetings.

And if you’re not familiar with Morgan Housel… he’s a writer that currently writes over at CollaborativeFund.com. And I will link to his blog in the show notes. But like I said before, he’s one of my favorite financial writers. And he just released a book called “The Psychology of Money,” which I’m extremely excited to read—I haven’t yet. And the reason for that is because I haven’t got it early. It just got released.

So usually, when I interview authors around a book release, the publisher will get in touch and send me an advanced copy. But since I didn’t actually interview Morgan, that didn’t happen. So I’m excited to read it just along with everybody else in the general public. But since it was just released, I haven’t done it yet. So I can’t really speak about the book, but it sounds excellent. And just like all of Morgan’s writing on finances, I am really looking forward to reading it.

So, I will put a link in the show notes to that as well, if you want to check that out.

Anyway, as for me, I am excited to introduce these two guys. And apologies for the audio quality. It sounds like Morgan was just calling in from his cell phone or something. And obviously, I wasn’t anticipating this to end up as a podcast. So apologies for not having the normal audio quality that you’re used to. But the discussion is interesting enough that I definitely think it’s worth it.

So, big thanks again to Morgan and Gouri for letting me do this and to the Bogleheads for letting me share their meeting presentation. And I hope you enjoy it as much as I did.

Gouri: How has CoVID challenged, affirmed and changed your beliefs, and are there new realizations and practices for you?

Morgan Housel: So, two things come to mind here: one is, something I’ve always believed, it just gets so driven home this year, is that the biggest risk in any year, in any era, and I think in almost any field, the biggest risk is always what no one is talking about.

So, we always, as investors, as people thinking about money, think about what is the biggest risk over the next year, the next ten years. And there are events that we can think about. There’s the coming election, there’s trade wars, there’s stimulus deals, CoVID-19, when are we going to get a vaccine… all these different things that we know and we can talk about. But in any given year, it’s always the case. And I truly mean it’s always the case. In any given year, the most important story in finance is something that no one could have possibly been talking about before it happened—whether that was CoVID-19 this year.

You know, people have been talking about pandemics for a long time—Bill Gates gave a TED Talk in 2015 warning about basically this exact event. But the timing and the magnitude of COVID-19 is not something that anyone could have known before it happened.

The same is, of course, true for September 11th, Pearl Harbor, the Great Depression, JFK being assassinated… all these big, huge, monumental events that really moved the needle, when you look back, you could say, “That event is all that matters.” So to speak, those events are always the one that you could not see coming.

And that fact that you couldn’t see them coming is what makes them different. It’s what makes them dangerous.

People are very good at preparing for known risks, preparing both financially and psychologically. People care financially, getting their cash flow in order, so to speak, but they prepare psychologically, so that when it comes, even if it’s a big event, it’s not shocking. It’s not jarring to them.

It’s very different for something like CoVID where, for the United States at least, it seems like there was about a three- or four-day period in early March where everyone doubt it. And very quickly, what seems like virtually overnight, businesses shut down, schools shut down, airports ground to a halt. It was such a shocking event that you can really distinguish—you know, pre-March and post-March were very different worlds.

That was the case for September 11th. We refer to it by the date because everything changed in one day. The world, September 10th, was very different from September 12th. Everything changed that day.

So, that’s always the case. And that’s been re-affirmed this year. And of course, it’s going to be the case going forward. People are more attuned to financial and economic risk right now than they have been in a very long time. So, more people than ever are looking ahead saying, “What’s going to happen next? What are the biggest economic risks for the rest of the year? What are the biggest CoVID risks?” without realizing that we learned this year is that the world is surprising. And the biggest event, the most monumental stuff that moves the needle is always going to be surprising.

So, the biggest risk for the next year, it’s something you and I and everyone else cannot be talking about right now because, by definition, we don’t know about it.

Gouri: So, building on that, to what extent, broadly speaking, not necessarily limited to this year and this election, but including this election, to what extent do you think politics matter? And any comment on this upcoming election?

Morgan: I think this was about 2010. I was at a conference, and I was listening to a banking lobbyist give a talk. And it was a really good talk. And he had been involved in presidential elections for, I think, 30 years at that point. And he made this quip that every single election that he had ever been involved with over those 30 years, every single election, people said, “This is the most important election of our lifetime.” And he made a joke that like, look at some point, it’s not. At some point, it’s not the most important election of our lives. It’s just this normal path of history.

Of course, in 2016, I used that example prior to the election of saying, “Look, this truly is the most important election of our lifetime.” That’s what it felt like in 2016. And now, I would say it again in 2020… this is the most important election of our lifetime. It always feels that way even if you say it every single time.

On one hand, the long history of one party saying, “If the other party wins, the whole country is going to collapse,” is really wrong. We can see—of course, not universally—Franklin Roosevelt is, by and large, by historians, viewed as one of the great presidents of our time. I know it’s a controversial statement. But in general, among historians, it tends to be true. He was so incredibly controversial at the time, particularly in 1932 when he was elected. The number of people who really thought that this was going to usher in an era of communism or fascism that was sweeping over Europe at the time was very, very high.

So, there’s a long history of people saying, “If this guy wins, then all bets are off! The country’s going to collapse.” There’s a long tradition of that.

There’s also a long tradition of investors saying, “If this party wins on either side, then buy these stocks. Well, here’s what the stock market is going to do next.” And those series of predictions that they tend to have, the worst track record of any group of economic predictions.

I mean, just the recent examples… when George W. Bush won in 2000, a very common narrative that made a lot of sense was Bush was going to deregulate the banks—so buy the bank stocks, and he’s going to have a tax cut, which is going to be good for travel, so buy the airline stocks. And I’m not making fun of that narrative because it made sense at the time. That’s a reasonable narrative to make.

Of course, by 2008, most of the airlines were bankrupt. And most of the banks were bankrupt as well. It turned out to be the worst investing situations you could have.

In 2008, when Barack Obama was elected, a common narrative was buy the solar companies because there’s going to be a big push for green energy. And of course, within years, most of the solar companies themselves were bankrupt. It turned out to be one of the worst trades that you can make.

A lot of people in 2016, there was this general idea that if Donald Trump wins, then terrible for the economy, terrible for Trump, for whatever reason that will be, terrible for the stock market. And the stock market […] since then.

It’s so easy to look back at these reasonable narratives that makes sense that turned out being the exact opposite, which I think is just the case that people tend to give the president on either side, on either party, more credit and more blame than they generally deserve.

Now, it’s not to say that the president is not powerful. But in the list of variables that matter in the stock market and in the economy, they’re lower down on that list than most people would think.

So there are other variables that matter a lot more.

Of course, I have my political beliefs—strong, political beliefs. I have my views about where I really want this election to go. But none of those affect how I manage money… yet, at least, I would say.

I think one of those dangerous things that investors can do is when they have very strong political beliefs—like a lot of us do—but they let those political beliefs guide how they invest particularly in the short term. That’s when things get really dangerous. I think there are few poisons to the investing process more potent than really strong political beliefs that you mix with your investing decisions.

Gouri: So we might consider doing the opposite of whatever the pundit say.

Morgan: If you have to make a bet, historically, that would be the better bet. The mind for most people is, if you are happy with your investing portfolio right now in September, you should be happy with it in the middle of November regardless of who wins. And if on November 4th, whatever the day after the election is, if you are trying to make huge changes to your portfolios, and you consider yourself to be a long-term investor, and you still want to make big changes to your portfolio on November 4—not to me, not for everyone, but in general—it’s increasing the odds that you’re going to make a regrettable decision down the road.

There’s so much history that goes against doing that and so much reason to believe that strong, political beliefs that influence your investing decisions just so often turn out wrong and regrettable. And to me, if you are a long-term investor, that means you are a long-term optimist. Now, I want to be investing for the next 20, or 30, or 40, or even 50 years. And therefore, what’s going to happen in the politics in the next four or eight years, by and large, is not going to have a tremendous impact on that.

Of course, you can think of situations where, because of any single president or congress or whatever it is, there is some sort of political catastrophe. There’s history of that—not just in the United States, but across the world. So it’s not black and white. But to me, the odds that I just want to let things compound in the next 30 years and not make short-term decisions based off who wins the elections are pretty overwhelming.

Gouri: Excellent! So you’re known for reading a ton of both current events and commentary as well as history. How do you separate signal from noise? And how do you, not just for reliable, existing sources, but signal from noise for new sources and opinions that differ?

Morgan: The first thing I would say is I don’t pretend like I’m any good at it or any better than anyone else. Everyone wants to separate the signal from the noise, but we are creatures of looking up confirmation bias, and looking for things particularly when we’re talking about history examples and little nuggets that concern what we want to believe, the view of the world that we want to have.

So, I won’t pretend like I or anyone can do well at that. But to me, the biggest thing with history is, there’s so much to learn from history, but most of what we want to learn are not the specific event. What we want to learn about, by and large, are the really broad events that teach you how to people think about behavior. And the really big, recurring events that tend to show up at multiple different parts of history, that’s what you should pay the most attention to.

Jason Zweig of the Wall Street Journal had this great idea. Why do people keep making so many financial blunders? Why do we go from bubble to bubble? Why can’t people learn their lesson, so to speak? And his idea is it’s not that people don’t learn their lesson, it’s that people learn too precise a lesson.

So, in 2000/2001, the lesson that people learned was “don’t buy expensive [TEX] stocks.” They learned a really precise lesson. They didn’t necessarily learn about boom and bust. They just learned this very precise lesson about dot-com [TEX] box. So a lot of those people moved towards Miami condos. And then when that blew up, the precise lesson that they learned was don’t buy Miami condos. And then, they moved on to bitcoin or gold or whatever it was.

So, they learn these very precise lessons without the really broad takeaway that has to do with human behavior.

So, when I look at history, it’s not poring over data and looking for correlation about when GDP does X, the stock market does Y. That’s one version of looking at history. But for me, I’m much more interested in the really broad takeaways about how people deal with greed and fear and what-not.

And to me, like some of the takeaways that are important to me are a) this idea that the world breaks every five to ten years. And if you go back historically, there’s almost no exceptions to that. But every five or ten years, not exactly on that time scale, but roughly about that on average, something happens in the world where everything grinds to a halt and a lot of the assumptions that people had about how the world works break.

So, we’re dealing with one right now with CoVID-19, but there is also the financial crisis of 2008, September 11th, the dot-com explosion, the fall of the Soviet Union, the inflation of the 1970s and ‘80s, JFK being assassinated, the racial tensions in the 1960s, the Great Depression, World War II. It goes on and on and on.

There is never a period where you can go five or ten years of calm. The world is constantly breaking. And that’s really important as an investor because, once you expect that to happen as just the normal course of events, even during a period where things do really well—

The stock market has done extraordinarily well over the past 60 years. So you’re betting on long-term optimism. But if you spend much time in history, you have to be a short-term pessimist because there is no period in history that avoids short-term pessimism. Pessimism is that constant, never-ending chain of bad news.

So, if you have that as a mindset, that long-term optimism is possible even if there’s constant, never-ending chain of short-term pessimism, then it helps you get through the short-term problem, the short-term breakages. And if something like CoVID-19 occurs, to me, it is shocking, I didn’t expect it, it’s brutal, it was scary, it still is scary, but I think it’s a little bit easier to deal with particularly as an investor if you realize that, over the long course of history, this is the kind of thing that happens even in the mid- to backdrop of a really extraordinary long-term growth.

It’s not intuitive to think that the world can break every five or ten years. Even during a period where, the last 50 years, the stock market has increased 200-fold, it’s not intuitive… to think. We either have those many problems, those many setbacks, deep, really, structural problems during a period where you have extraordinary growth that you can take advantage of. It’s not intuitive, but that’s how history works over time.

So, I think those kinds of really broad behaviors, those broad takeaways about behaviors, are what people should take away from history, rather than the specific events and learning too precise a lesson from what’s happened in the past.

Gouri: So switching to you personally for a few minutes, you’ve mentioned that you’re working towards financial independence. I’m curious… I know you clearly love your work. You’re really good at it. You chose it. You honed your skills. How do you envision financial independence? What would you do more of or less of? And what would you give up and what would you really take on?

Morgan: I think there’s a spectrum of financial independence, obviously. It’s not necessarily black and white. There’s that one level where if you just have a little bit of savings, you’re a little bit more independent than you were versus someone who is just solely relying on the kindness of strangers. If you are good at your job, that’s a level of independence. So there’s a big spectrum of it.

To me, the level that really matters is when you can, for various reasons, just wake up and virtually, any day, say, “I can do whatever I want today.” You can work really hard at a work that you’re really passionate about if you want to do that. But if you wanted to take time off, you can do that too. You want to hang out with your family, you can do that too. It’s just maintaining control over your schedule.

And there’s a lot of different ways to do that. That roughly falls into the FIRE framework—financial independence retire early—which is something that I like in the sense of financial independence. But “retire early” is almost this idea that you are committing yourself to not working again, which is where it gets a little rough for me because, most people, even if they have full control over what they do, most able-bodied, smart people who are underage 65 would say are going to wake up most days and say, “I want to do good work today. I want to go to work. I want to put my brain to work, put my muscles to work and be productive in society.” That’s what most people want to do.

But I think just as long as you can do that on your own terms, doing the projects that you like, when you want to do them, who you want to do them with, for as long as you want to do them with, and then you can stop whenever you want, that to me is the highest dividend that money paid.

And it’s really important because a lot of financial material stuff, which is not—this is where people get accustomed to it over time. It’s not that a fancy car or a nice house is not going to make you happy, but you tend to get accustomed to it, whereas controlling your time is something that gives most people an enduring level of happiness. And every day that you can wake up every morning and say, “I can do whatever I want today. I can go to work, but I could quit. I can retire. I can do something else,” every day that you have that is going to give you a lasting level of happiness that it’s hard to get used to over time. It tends to be enduring over time.

And the opposite of that—waking up every morning and realizing that you are on someone else’s schedule, that someone is going to tell you when to go to work, where to go to work, what to do at work, when you can eat lunch, when you can go home, that tends to be just a level of dependence on other people that brings a lasting level of angst and unhappiness and stress.

So, that’s all I care about with financial independence, is that my career moves more towards this idea where I can do whatever I want. And what I want to do is write—which is what I’ve always done for work. As long as I can move and move toward this idea of “Look, I’m going to write when I want to. I’m going to write about whenever I want to. I’m going to do it for as long as I want to. I’m going to publish it where I want to,” that to me is what really matters in terms of financial independence. But I’m always going to keep writing because it’s what I love to do and what I’m passionate about.

Gouri: Excellent, excellent! How did your childhood and your parents influence your current work?

Morgan: So, I wrote about this in the book. My father started his career later. He started his undergraduate college when he was 30 and had three kids. I’m the youngest of three. So, he started his undergraduate college a few months after I was born. And he became a doctor. He became an MD when I was in fourth grade or something like that.

So, he started really late. And that was important because, in my early childhood, the time I was born through, let’s call it fourth grade, we were very, very poor. So my parents were students. We were living off of grants and student loans and we had no money. We had nothing. So I got to see that side.

Of course, when you’re young and you haven’t experienced anything else, you don’t know that you’re poor. I had a great childhood. I liked playing with my parents and playing in the backyard. And we went camping. But you don’t know what you’re missing.

But then my father became a doctor when I was in fourth grade. And we moved on to a much more comfortable way of living. He had a doctor’s salary and that was what we had. We bought a nicer house. We went on vacations. There was a very stark change that happened when he became a doctor, as you can imagine.

But what was really important for them is that the forced frugality that my parents had when they were students, trying to raise three kids off of grants and student loans, that forced frugality stuck with them even after their incomes rose, after my father became a doctor.

So, even as a doctor, we lived a more comfortable life, but they were very frugal, and their savings rate was very high. And what that led them to after 25 years of working was my dad basically woke up one day and said, “I don’t want to work anymore. I’m ready to retire. I’m ready to move on.” And he just did.

And he was able to do that. He had that level of independence because he had a high savings rate from his old career that let him do that.

So, that had a big influence on me just like in the last five or ten years. It didn’t really hit me until that event occurred in the last decade that, wow, that was something really important, that this frugality that’s stuck with them for his whole life gave him this decision, led him to make this decision on his own terms whenever he wanted to in a way that was so meaningful and important in life that I wanted to do that.

So, growing up with that level of frugality just as the base case for me stuck with me. And I don’t necessarily consider myself frugal because I buy whatever I want, but my wants and desires aren’t that great. They’re not that high.